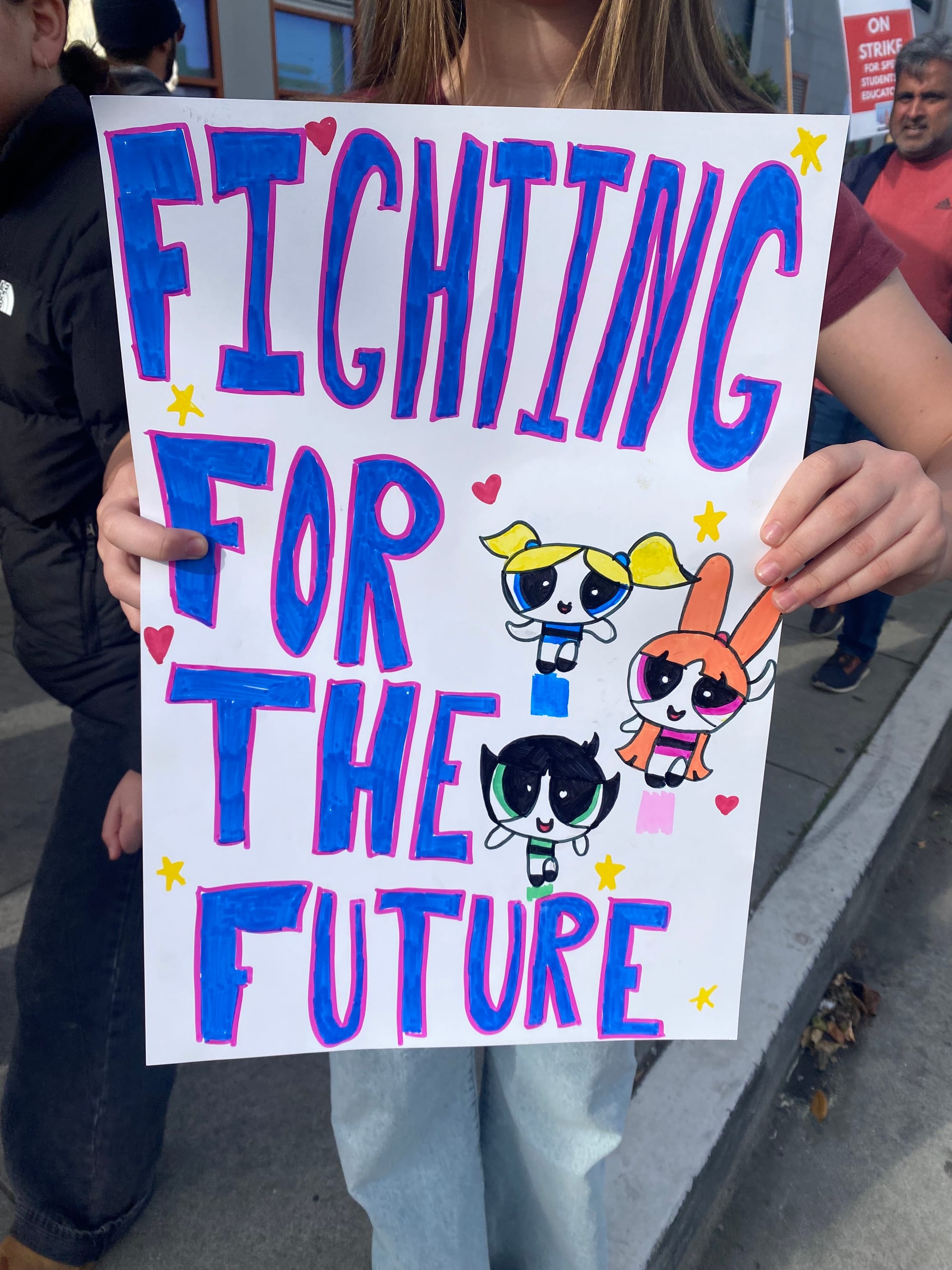

“We Are Out Here Fighting For What We Need”

San Francisco special education teachers tell us why they’re striking.

San Francisco special education teachers tell us why they’re striking.

In the run-up to today’s strike by San Francisco teachers, headlines highlighted its historic nature. In 1978, the last time San Francisco teachers went on strike, it was a response to the passage of Proposition 13 and the subsequent gutting of tax revenue for public education. Once again, the current teachers’ strike arrives at a time where state-wide fights surrounding wealth consolidation, public-private partnerships and state expenditures are heating up.

The gravity of the situation was palpable on the picket line at Willie L. Brown Jr. Middle School Monday morning, where roughly 70 strikers and supporters were gathered. “We want smaller caseloads now!” the group chanted, a reference to the unsustainably large number of students assigned to an individual special education teacher or paraeducator, who is also known as a para.

When Grace Del Toro first started teaching at Dr. Charles R. Drew Elementary three years ago, the school did not have a permanent special ed teacher. They did not get one until last year, leaving many students without support, and general education teachers scrambling to pick up the slack.

Despite the position being filled, Charles Drew still bears the burden of an understaffed special ed contingent and ballooning class sizes. “Past first grade there’s no para support,” Del Toro said. “Its really hard to plan for 29 kids and make sure they’re all accommodated… Even if we do have paras that we can split among the staff, I don’t even want to ask them for support because it's too much,” Del Toro continued, "It's not fair.”

Paraeducators work as one-to-one aides for students with disabilities and are some of the lowest paid teaching professionals in the district. The teachers union, United Educators of San Francisco (UESF), is proposing the district give them a 14% raise. “Making sure we’re retaining paras with competitive pay is a big deal,” said Emma Smith, a former para and current sixth grade history teacher at Willie Brown. In 2023, SFUSD had 200 vacant paraeducator positions — a shortage UESF links to the city’s affordability crisis. “A lot of our paras live outside the city,” Del Toro said, noting she also knows paras who work multiple jobs.

Paraeducator work is grueling, unglamorous and rarely acknowledged. “When I have conversations with my friends and community members, they don’t even know that paras exist,” Del Toro said.

At an afternoon rally at Civic Center, Ruby Tsang, a paraeducator at Lincoln High School, described the ways being a para can be emotionally exhausting. “Sometimes in our line of work, they don’t survive,” she said.

Tsang works with an Extensive Support Needs class, meaning she helps students who might be nonverbal, incontinent, or eat through a feeding tube. “I might have to go visit someone in hospice or go to a funeral,” she said, becoming emotional. “We don’t want to be on strike, we don’t want to be out of the classroom. We want to be with the children, but we are out here fighting for what we need.”

“We don’t want to be on strike, we don’t want to be out of the classroom. We want to be with the children, but we are out here fighting for what we need.”

Tsang is also one of many SFUSD educators paying exorbitant premiums for family health insurance, another crucial sticking point at the bargaining table. In recent years, she went from paying $700 a month to $1200.

Katie Ripley, a seventh grade English teacher at Willie Brown, described how high family healthcare costs have complicated her divorce. “We decided that it's completely impossible to put our kids on my health insurance because it would cost $800 a month on top of what I pay for myself.” Ripley said that a family of four on the district’s health plan pays $1,500 per month.

Smith and Ripley said that instability within the administration begets instability within schools. “Even the small things are not being done correctly,” Ripley said. SFUSD spends a disproportionate amount on its administrative staff, something UESF has been talking about for years. Research conducted by the union reveals that the district spends “96 percent more per student on central office supervisory staff than the state average.”

As with instability, misaligned priorities also have a trickle-down effect in SFUSD, teachers said. “In America, which is a very capitalist society, public goods and public entities are slowly disappearing,” Del Toro said. She expressed that she felt capitalism, combined with a Board of Education occupied by non-educators, has warped what we understand education to be.

Just a few weeks ago, Governor Newsom vowed to block the Billionaire Tax Act, a one-time 5% tax on individuals with a net worth of over a billion dollars. And in the eleventh hour of contract negotiations before the strike, the school board nearly greenlit a deal with Open AI. The stakes for the SFUSD budget — and the teachers and working class families it serves — have never been higher.