SCENE REPORT: Bay Area Marches in Solidarity with Minneapolis

Protests against ICE have spread to the Bay. We wanted to hear directly from Bay Area residents who turned out in East Oakland to support the surging movement in Minneapolis.

From resisting the war in Vietnam to tenant organizing and solidarity with Palestine

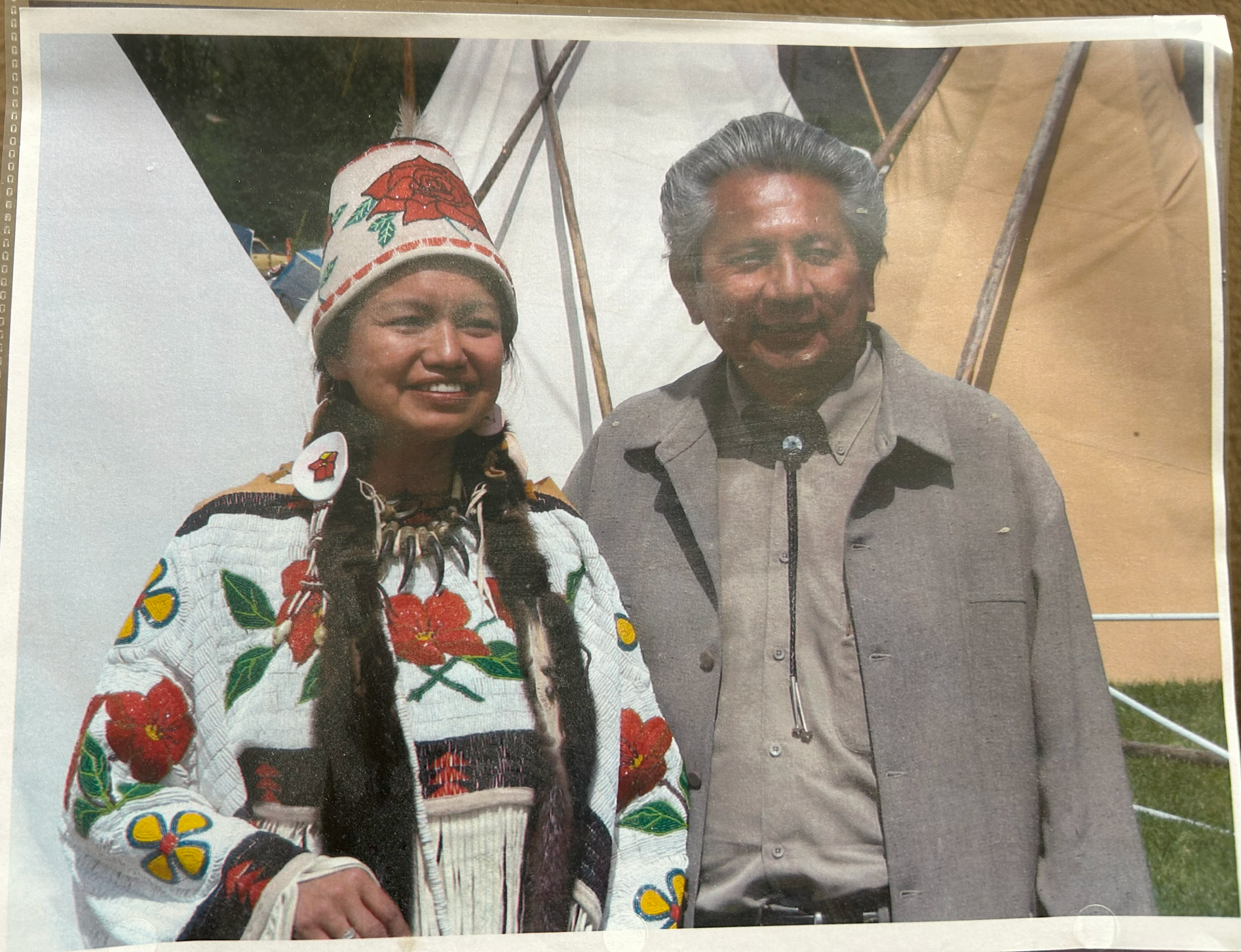

Deni Leonard is a 79-year-old indigenous elder, and a member of tenants union Tenant and Neighborhood Councils (TANC) local in San Francisco. He sought out help when his landlords, Edmund and Hermancia Lai, threatened him with eviction. On June 8, about 20 organizers from TANC and West Side Tenant Association (WSTA) arrived at the Lai’s house in San Francisco’s Outer Sunset to protest his eviction. On June 9, the landlords settled: Leonard could stay in his home. This was not Leonard’s first fight — nor his most significant.

Leonard is a Vietnam War resister, who sacrificed and took incredible risks to maintain his principles and refuse deployment. He was instrumental in the closure of the Presidio stockade in 1969, when the physical abuse he and other political prisoners suffered there was publicized.

Leonard sat down with Bay Area Current to discuss his politics as an indigenous person, his stories from the anti-war movement, and his reflections on the tenant movement.

Nate Hale: In your own words, how did you first become engaged in politics?

Deni Leonard: Well, my mother influenced me. When I was in high school, Madras High School in Oregon, there was a lot of prejudice against the American Indians as well as Black, Hispanic and Asian people. So I told her over breakfast that the teachers were getting upset with me, when I would explain that there was racism in the school’s academic programs. She told me that, because we're so small as a population, American Indians need to find others — Hispanic, Asian, African American, and whites who also are in poverty — who are being discriminated against, and collectively work with them to build a program to get rid of discrimination and prejudices.

NH: So was your mom always political, or was this just her thinking?

DL: No. That was just her logic.

NH: We've talked before about your upbringing on the Warm Springs reservation. You mentioned hunting trips in accordance with indigenous tradition, you also climbed Mount Hood when you were young, about fourteen, and I understand that’s related to your indigenous culture and where you lived?

DL: My elders told me that, when the treaties and negotiations for our land were being made, some of the warriors went up the mountain to look at the land. When they came down they told their leaders, “these areas have water, they have animals, they have food.” So in making the treaties, the reservation borders were premised on going up Mount Hood to make sure we had food, water, and housing. We had plants and vegetables for making traditional protection. And we had areas for our horses and cattle to roam.

NH: That's the kind of thing I was thinking about because, being indigenous — it's all-encompassing, right? Being indigenous entails a whole way of life. I'm not indigenous — I'm Filipino–so it's hard to dip my toes in because it’s a whole worldview. But I have prepared a question: did you have specific formative moments? Is there a way you might distill your experience, for a nonindigenous audience?

DL: Well, I have very strong memories of going to grade school on the reservation, where the teachers or counselors would pick on my fellow tribal members. I would stand up to them, and then I would get beaten up, and sometimes they would pull me out of line and hit me with their fists. I was knocked down the stairs and put in the basement. They would lock the door and, with no light, they'd keep me there all day as punishment.

NH: That’s terrible. So the violence was there very early, even in grade school?

DL: Yeah, but I never stopped, I would go back and take him on again. They were Bureau of Indian Affairs people.

Nate: That makes sense. I'll add, for the sake of conversation, that it’s remarkable how the Bureau of Indian Affairs is just another regime of state violence.

Deni: Yeah, exactly.

NH: That connects to my next question. How did you first learn about the genocide and oppression of Native peoples?

DL: Initially, when I was drafted into the army, there were different events. In basic training, I saw pictures in the sergeants’ offices, all over the walls — they depicted American Indians being killed, and the abuse of American Indians by soldiers. So that got me thinking, “If that's what they're bragging about, this must be what they've been doing all along.” I began to think about what kind of schooling I had, that kind of brutality. I began to think the truth is all hidden — I'm going to find out what it is.

NH: OK. So how, then, did you decide to resist deployment to the Vietnam War?

DL: I was already involved in the civil rights struggle — then JFK was shot and killed when I was in high school, and Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles while I was in the army. I had met Bobby Kennedy because he came to look at the reservation, the boarding schools, and I had a chance to talk to him. So I got really upset about that [the assassination], you know? I knew there was going to be a cover up of everything. So I said, well, this is a pattern —it must be a big pattern. I decided to look into what was happening in Vietnam. And when I compared Vietnam to the genocide of the American Indians, I saw that the military was doing the same thing to the Vietnamese that they had done to us. Why should I go over there with the rifle, to “protect us”?

NH: So you connected these different pieces of evidence. And then what was it like? Did you have a moment of decision?

DL: I decided that if I went, I would be a coward — I would not have my spiritual strength. It would go against everything I was taught about not killing other people, and protecting my people. So I decided to resist deployment.

I was going to be deployed to Vietnam from Oakland. And so I'm sitting there at the base — I'm supposed to catch a vehicle and be shipped to Vietnam. In the middle of the night, I climbed out of my barracks and got off the base. I didn’t know many people there, only a couple of my buddies who were in the Bay Area that I went to college with. So I told them I needed assistance. I didn’t tell them the whole story, just that I didn't have a place to stay. And they helped me. I stayed with them and a couple other friends for a while. Then the FBI began chasing my friends and family and interviewing them, asking them where I was. I didn't have any money, so I had to borrow some. I couldn’t keep surviving.

When I was in high school, ABC had done a documentary on me called Too Many Fathers, and I learned the producers had moved to San Francisco. So I figured well, if they're going to shit on me, I'm going to have as much exposure as possible. I went and found the two producers — they were on KTVU TV in the city. I told them my situation.

They said, “Well, Deni, let's write a letter about how you feel about the Vietnam War and American Indians.” Which is what I did, in their offices in the TV studio. They put me in a motel on Lombard Street and said “Tomorrow we're going to get a camera crew together and we will drive you down to the Presidio, so you can give yourself up.” Then the next day they filmed me as I turned myself in.

The MPs [military police] came and threw the crew out. Then they took me into the MP station. There were about four MPs cussing me out and giving me shit about being a coward and not going, you know?

And then about an hour in, the television producer came back and knocked on the door. The MP said “we told you you can't be in here.”

The producer said, “Oh, I'm sorry, sir. We forgot to take the microphone off Mr. Leonard.” So they had all that conversation recorded with me! So immediately the MPs began being nice, bringing me food.

They put me in a basement prison at the Presidio stockade. There were three other American Indians in the stockade also, they were there for actual criminal things. But we became good friends.

I was prosecuted in one of the buildings at the Presidio, which I pass every time I take a bus to the Presidio. They took me down to the military judges. “Well, Mr. Leonard, are you claiming conscientious objector status?” I said, “No, I'm not. I'm not going to put other people in jeopardy for an illegal act of invading Vietnam and killing people. I'm not a conscientious objector.”

And the judge says, “if you're not, are you politically saying that you're against what we are doing?” I said “yes, absolutely.”

NH: The colonization and genocide of Palestine is ongoing, and you're in a good position to reflect on that because of your experience with the Vietnam War. Do you have any thoughts on that?

DL: Yes, I recall the medicine people who are spiritual carriers. Henry Crow Dog, for example, from the Lakota tribe. His son was Leonard Crow Dog, who was the spiritual guide for the American Indian movement. I met them and they told me to study math. They said, “why don't you study math, Deni?” They’re like 80 years old talking, educating me.

They said: “In math everything comes out — two and two is four. That's a pure way through which you can look at the truth. Math will tell the truth and it can be applied to other areas. Make sure you look at the problems you are having, and look at how the balance is coming forward. If the balance isn't there, that means whatever you're doing — your opinions are incorrect. You have to find another answer. You have to find an original cause. Then, the original cause is what you attack.”

Smart people are disguising how to solve the problem, because they're making profits. They have ways that they’re getting you not to look at what they’ve done.

I look at Palestine, and then Netanyahu, and he is using our country to support the violent genocide of the Palestinians. And it's a false premise because their violence is a genocidal pact. If we as a country accept that, then there will be very little left for us in the world, because now we will have the Nazis recreated in the United States. I connect that with the election and the idea that the right wing paid tremendous amounts of money so that the majority of caucasians supported the Republicans.

Then there’s the Supreme Court being packed with right-wing people. That's almost exactly what Hitler was doing. Putting all that together with the regime of Germany. And so now it's being replicated in the United States.

Why don't the media call the Israeli leader a Nazi? Why are they not coming out saying, you know, this is what happened in Poland? This is what they did in Europe — what they're doing now. During World War II, the media in the United States wasn’t talking about the Holocaust (or what would later be called it). They were letting it go. That's exactly what they're doing now with Netanyahu. So all this stuff is coming back. It's replicating itself.

NH: You've attended a number of San Francisco TANC meetings and Westside Tenants Association meetings at this point. How would you characterize the differences, if any, between the movement spaces of the late 60s and 70s and now? Where do you think we are politically and organizationally?

DL: Well, for one, during that time there were a lot of attorneys that were very, very liberal. When I was in the anti-war movement Lee Harvey Oswald's attorney, Mark Lane, became one of the attorneys backing me. They would fly in for different things that I had. And they had some very influential leaders that were helping them.

Here and now, we see the absence of a lot of these attorneys. Now some of them have a philosophy and the consciousness of right and wrong, but they don't have the courage to step up and do something. But just look at my tenant attorney — he's being paid to protect the poor and vulnerable. Instead, he's taken the money from the nonprofit and he's trying to streamline resolutions that have nothing to do with justice. He’s trying to expedite the case. The attorneys now have a different concept of what's going on, so it will take a big political change to have these things come together.

When I look at TANC, during meetings I thought “they all have the philosophy for social justice and they have an ability to sustain themselves when they're going to be attacked. They support each other even when the biggest real estate corporations are coming after them.” I think that's what made me feel stronger — because if these young people in TANC can do that, I should not worry about anything, because I need to have faith that we’re going to come together and we're going to work on a solution. And if we don't know what the solution is, we're going to find it together. This TANC idea will grow and we have to all work to make it grow.

I kept thinking, while listening to people’s different problems — this is how everything was during Vietnam. Nobody would do anything because it was too big, the government's going to come after us. And then we kept on doing it and kept on doing it. That’s what I got from my old experiences. We have to keep doing it over and over and over and make sure that, even when we are being attacked, look out and find resources that we can utilize.

So then I look to people who say, “OK, we're going to organize and we're going to be strong together.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. You can support Deni's efforts to be designated a Cultural Legacy, given his status as an Indigenous elder and Vietnam War resister, by completing this form. This designation will grant Deni permanent rent relief to stay in his apartment.