TENTATIVE AGREEMENT REACHED: Oakland Teachers' Strike Off For Now, But Cuts Loom

Teachers and staff will decide if they accept the contract as Oakland Education Association promises to fight a 10% reduction in OUSD staff.

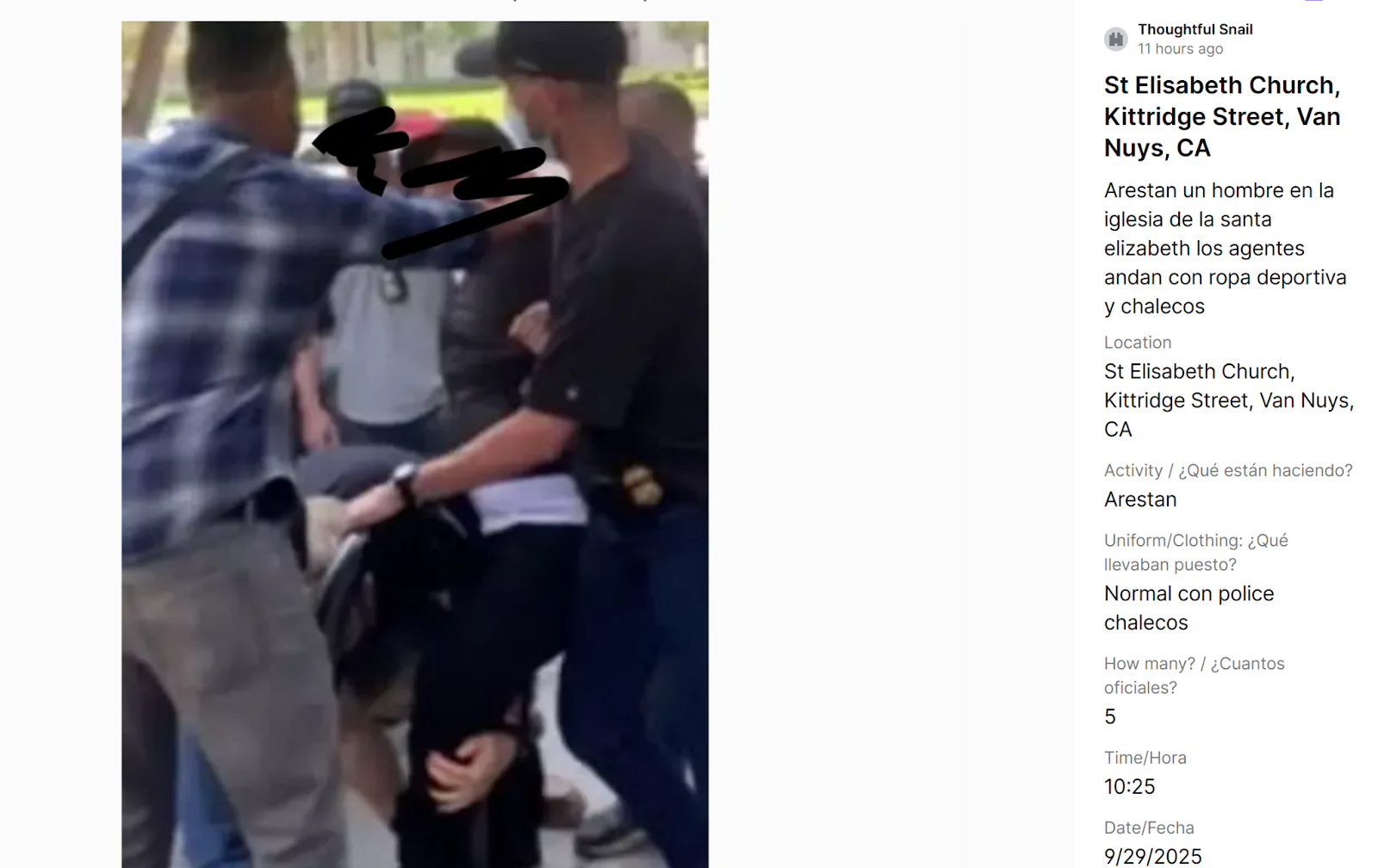

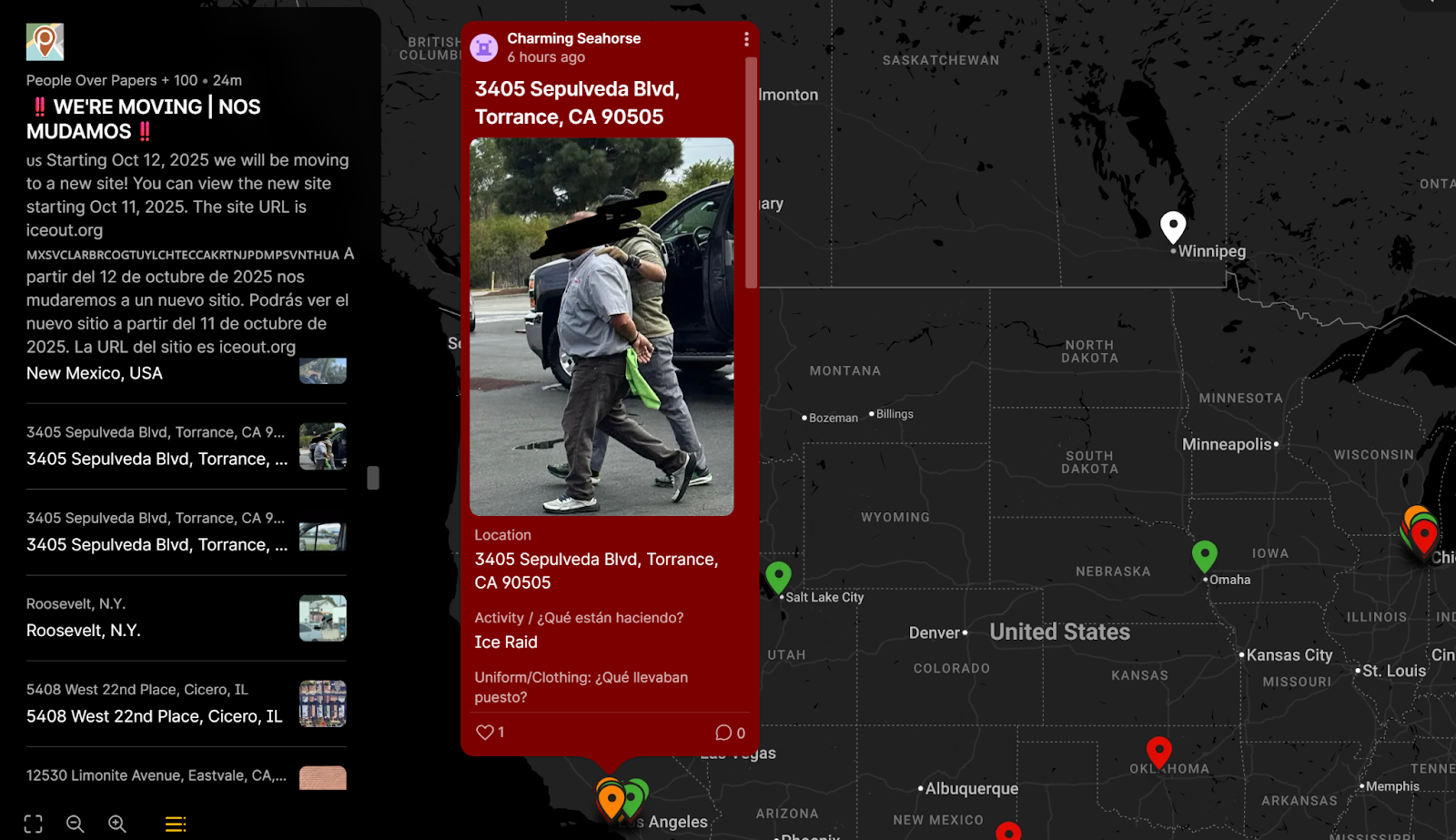

People Over Papers' site map offers a glimpse into the informal media people use to warn neighbors when systems of formal confirmation can't match the need.

Hovering your cursor over a pin in the north edges of Long Beach, a click reveals a photo of four masked men in body armor forcing a young man into a van. The report, a moderator on the site People Over Papers explained, has not been verified. Scrolling to a red pin directly beside it, however, you can see another angle of the cops handcuffing the same man. This has been confirmed and reposted from the Facebook account of Unión del Barrio, an immigrant defense organization based in Southern California. Yet another pin opens a screenshot from Instagram warning people of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) presence. Text scrawled over the photo explains: “hitting car washes again!” Just a month ago, immigration agents raided another car wash in Long Beach.

These are three reports among hundreds that can be found on the same day at People Over Papers, an English- and Spanish-language website dedicated to posting daily sightings of immigration agents on a map that covers the country. The project launched in January of this year. After a surge in submissions that followed the federal occupation of Los Angeles in June, they are expanding their operation.

The site features original submissions as well as those reposted from social media that track suspected ICE activity in their neighborhoods, and the number of users has increased — to between 200 to 300 thousand visits per day with over 1,000 submissions per week just as immigration police presence has escalated across the country.

“There’s a virality that happens with the map,” said Celeste, one of two founders who identified herself for this piece only by her first name. As armed agents occupied parks and courthouses across Los Angeles, the site received over 1000 reports a day.

That traffic weighed on the site. “It was lagging really bad,” Celeste recalled. Now, she says, they are raising money to support their new site that can sustain the broad demand that is not likely to recede, and with an app that users can consult.

That move to their new site became urgent on October 5 when Padlet, the service that originally hosted the map, abruptly shut it down. Padlet claimed in a message to Celeste that the shutdown was due to “violations of our content policy,” and did not provide more details, though the reason may lie in far-right agitator Laura Loomer’s tweet to the CEO demanding they shut down People Over Papers three days earlier. Padlet has not responded for comment.

People Over Papers hasn’t been the only target of this repression by insinuation. Apple moved quickly to follow Department of Justice requests to drop ICEBlock, an app that lets users share ICE sightings, from its App Store early this month.

Celeste envisioned the project as a way to confront the “information overload” of posts that warned of ICE presence in the early months of the current Trump administration and reduce it to an easily navigable map. Moderators of the site confront that information overload in the torrent of junk submissions. Maisie, one such moderator who is also identified by her first name for this article, sifts out AI-generated photos and videos in spam reports. Some submissions she’s received, like “an AI photo of Bernie Sanders,” seem “very intentional” as an effort to obstruct their work.

Submissions that are timely, have some evidence, and aren’t AI slop make it to the site. The vast majority of pins that mark those sightings on the map are not confirmed, and that sets People Over Papers apart from most local ICE-spotting hotlines. Still, the moderators work with local groups like Unión del Barrio to confirm sightings by getting eyes on the scene. “The only way we truly confirm submissions are with those local trusted community groups,” Maisie noted.

Alongside those groups with volunteers on the ground, the map of submissions gives a glimpse into a digital landscape of private Facebook groups, WhatsApp groups, Signal chats and subreddits where neighbors alert one another. The video doesn't always come from activists searching for it: Ring doorbell recordings and people coming home from work, Maisie said, are common sources for the footage.

The site works differently from local hotlines where people can call to spot ICE activity and, in some instances, seek advice or legal support in case of a confrontation. Celeste insisted that their map “is not a replacement” for a hotline, which may be able to respond to ICE encounters and connect victims with legal support.

That includes the hotline run by the Alameda County Immigration Legal Education Partnership (ACILEP). ACILEP trains “hundreds of volunteers” to verify reports they receive, according to Angel Ibarra, a program manager at the Centro Legal de la Raza, which administers ACILEP. These volunteers “go to the location, they verify what’s happening, they speak to the community.” When there is confirmed ICE presence — like a raid that led to the arrest of at least six people in East Oakland on August 12 or a traffic stop that became a detainment on September 17 — they post an alert to social media. Those posts on Instagram stand out among dozens that verify reported sightings were not, in fact, ICE.

Not all sightings can be verified, however, since the hotline operates from 6am to 6pm Mondays through Fridays. “We still monitor calls and voicemails” outside those hours, Ibarra explained, “we ask that folks still leave voicemails.” Local activists have demanded the county fund the hotline to run 24/7, and some county supervisors have expressed their support for the idea.

Not everyone working on the frontlines of ICE identification and immigrant defense agrees that unconfirmed reports deserve to be publicized. Celeste acknowledges that “some disagree that this should be made publicly available” given the possibility of “fear running rampant through their community.”

Still, with limited reach and operation, not everyone will think to turn to the hotlines, or be able to. ”If this information isn’t made public,” Celeste maintains, “people aren’t aware that people are being taken.” She wants People Over Papers to send submissions to receive confirmation from rapid response networks “that lean toward our perspective” when it comes to posting sightings.

Cutting down information overload of unverified sightings scattered across videos on social media was the goal when the founders launched People Over Papers. It’s also why Maisie joined the project: ”I was looking for resources for my girlfriend, she’s on the DACA program.” Sifting online, though, she found it “really hard to figure out what were real verifiable sightings.” It was understandable why people would post anything since, Maisie recalled, “people were terrified.”

That terror has sprung up again and again with each new city that becomes the next target. The site maintains weekly maps of submissions, and those pins tell a story of surging ICE presence and the fear that both precedes and follows it. On September 2, the day Trump threatened a federal occupation of Chicago, People Over Papers logged one sighting across the metro area. One week later, there were seventeen.