SCENE REPORT: Bay Area Marches in Solidarity with Minneapolis

Protests against ICE have spread to the Bay. We wanted to hear directly from Bay Area residents who turned out in East Oakland to support the surging movement in Minneapolis.

Mam, an endangered Mayan language nearly 2,600 years old, is blossoming in Oakland’s working-class communities.

Mam is one of the fastest growing languages in the East Bay — Oakland Unified School District reported over 1,100 students speak Mam at home — and its speakers are mostly working-class migrants from Guatemala and parts of Mexico. Many significant fightbacks by workers have included a vast diversity of people who speak different languages and bring to the struggle diverse criticisms of capitalism. To understand Mam and its background, I sat down with Javier Armas, author of Mam History: Oakland Notes on the History of the Mayan-Mam Language.

Armas was born and raised in Oakland. He’s a historian and educator, has taught history for over ten years in Bay Area high schools, and he recently started teaching history at Laney college.

Justin Gilmore: Javier, before we talk about your book on Mam language and history, could you talk about where you are coming from? What motivated you to look into Mam?

Javier Armas: Well that’s a big question. I was teaching Mayan mathematics at Oakland Technical High School then Skyline High School. At Skyline, all these students told me they spoke a Mayan language called Mam, while I was teaching them my Mayan mathematics unit. I then heard them speak Mam with their parents and then saw the magnitude of Mam students in Oakland. As a historian I sought the history of Mam, which did not exist, just linguistic anthropology. So at Skyline — myself with seven or so Mam students — we started a historical Mam research group in October 2023, reading one to two academic articles a week on Mam or Mayan society. Our project was to create the first introductory level history of the Mam language.

JG: Why is understanding Mam language history important for those of us in the Bay?

JA: Mam is a language older than both English and Spanish. Language embodies knowledge, culture, and history. Thus, the Mam language embodies an incredible pre-Hispanic history that is assumed to have died during Spanish colonialism. That narrative is part of the colonial project. Mayan Mam residents — for an array of political, economic, and cultural factors — have made Oakland their base, transforming the Fruitvale. If one wants to understand modern Oakland and its residents, one must understand the Mam community as its culture, not simply Guatemalans who “have a dialect” as it’s often referenced. As Oakland and urban cities across the US shift demographics, ancient Mayan cultures are blooming in proletarian—meaning, working class—spaces. If you want to organize the working class, you have to see its changing composition and its unique cultural history, and how this is all linked to what the Americas was before European arrival.

JG: What’s the relationship, if any, between Mam language in Oakland and social movements?

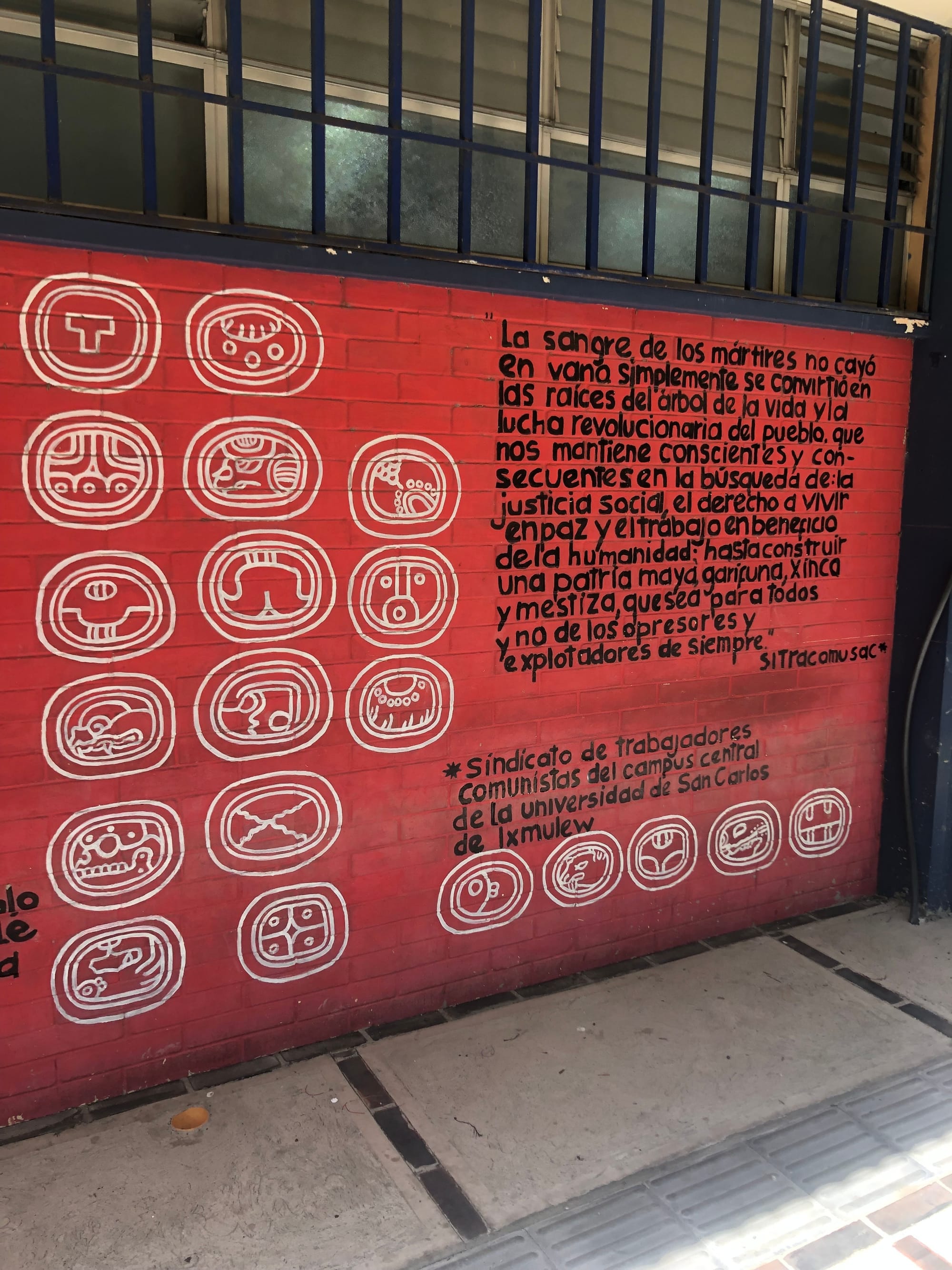

JA: There is a distrust between the Mam community and other social groups, including and especially landlord-positioned Guatemalan Ladinos who collaborated with the Guatemalan government and military in massacring Mayan communities in Guatemala from 1954 to 1996. The United Nations ruled this as a genocide in 1984. Mam community members slowly immigrated into working-class occupations in construction, housecleaning, and the food industry. Mam members are not mobilized by classical Latino and “People Of Color” identitarian categories and often do not attend the Latino student club in Oakland high schools. Fast forward to today, Mam community members experience extreme exploitation like wage theft. They are abused for not speaking English or Spanish, and articulate these abuses in their own spaces. Informal committees, especially a welfare system stemming from Todos Santos, a Mexican town that has its own dialect of Mam, meet to support the welfare of their community. These organizations are like incipient unions, and could collaborate with rank-and-file organizations, such as Tenant And Neighborhood Councils (TANC).

It’s a very proletarian culture that mixes with Guatemalan cultural practices, Mexican cultural practices, and now American ones. Mam community members have carved out spaces and created new businesses around Oakland that serve the Guatemalan population. If you go to Foothill and Fruitvale, you will see five to six small food businesses from Central American countries. Most of the Guatemalan ones speak Mam and display Mayan Mam cultural items. If you walk into a Guatelinda store in the Fruitvale, you will probably overhear Mam. If the workers think you speak Spanish, they will then shift to Spanish. In Oakland ten years ago, September 16, [which is] Mexican Independence Day, was mainly Mexican flags. Central American and Guatemalan Independence is September 15, so it’s celebrated at the same time. These last years Guatemalan flags outnumbered Mexican flags, pointing to a cultural, demographic shift in the Latino community.

JG: You are a public educator, and many public students speak Mam. How is the language being treated in Oakland’s public schools? Has the administration been interested in supporting Mam language speakers?

JA: School administration does absolutely nothing for the Mam community and simply counts them as Guatemalan, continuing to erase their Mayan identity. Fremont High School had the first Mayan-Mam group, with its own graduation. But at the district-wide level, they are deeply neglected. That’s why I wrote the book Mam History. It is an 11th/12th grade history book to introduce students to Mam history. I have been trying to get the Administration to get behind my book and distribute it in the classroom, and that’s a long, complex battle. It is a big battle to get admin to support the Mam student body, especially amid federal attacks on diversity.

JG: Your book frames the language through its cultural and political history. Why is that approach important?

JA: Books and indigenous archives were destroyed by Spanish colonialism. The Mayans had thousands of books, but all but four were burned. So we looked at how linguistic anthropologists understood the culture through the Mam language.

Most languages that are threatened with extinction are indigenous languages. Two out of the thirty-two Mayan languages are extinct. Mam is considered an endangered language.

Nora England produced so much work on Mam from a linguistic anthropological perspective crediting an array of local Mam scholars in the process. We [Armas and two Oakland Unified School district students] then charted out that linguistic data and attempted to historicize it. Since archives did not exist we have to use other mediums to look at pre-Hispanic history. Powerful languages have historians who write out their history while historians have just begun to historicize indigenous languages. Most languages that are threatened with extinction are indigenous languages. Two out of the thirty-two Mayan languages are extinct. Mam is considered an endangered language. This book is a nudge to get the ball rolling in that direction of historians taking seriously indigenous languages and their epistemological value. History of languages should not be confined to European or imperial languages, especially when framing the Americas.

JG: Any final thoughts? Or something you want Current readers to know?

JA: The Mayan society developed sophisticated societies with early usage of zero and advanced calendrical applications from astronomy. Its preclassic society was notably very equitable, mixing with Olmec and Zapotec cultures. Karl Marx was interested in native American societies at the end of his life. Thinking about how Native societies operated complex cultures with far less exploitation than our given system adds material culture to Marxist theory, generating a framework of how a society can work beyond capitalism. The 1960s ushered the first discussions between Marxism and indigeneity that continued sparingly up to the present. Peruvian Marxist Mariátegui made the most foundational synthesis between Marxism and the indigenous question, influencing a new generation of Latin American Marxists. Building towards a modern synthesis of indigenous thought and Marxism has profound revolutionary potential in creating new breakthroughs in critical thought for emerging revolutionary movements. This is especially important for young proletarians that have both indigenous ancestry and working class conditions.