Bay Area Chinese Leftists Are Making Language Political

We were in a very Chinese time in our lives. We decided to do something about it.

We attended SF Tech Week's block party for tech's supposed do-gooders. We couldn't find the party. Nor the good.

The gates to SPARK Social SF opened at three in the afternoon. I headed into this food truck park in Mission Bay to find it empty of techies but full of service workers in black, or hidden behind the sheen of windows in food trucks. Music blasted on an empty astroturf lawn. People slowly filed in, ice cream cones often in hand. I watched a graffiti artist paint a mural which would eventually read “Humanity Hardwired.”

The event was one of over a thousand happening as part of San Francisco’s annual Tech Week, a time when tech workers, venture capitalists, founders and the like come together to talk about new “innovations,” and their implications in the tech industry. At least that’s how it was advertised.

But why were we here at this particular event? Well, to slow down the progression of artificial intelligence, of course. This block party, put on by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar’s part-philanthropy part-venture capital project, Omidyar Network, was billed as an event about “responsible tech.” Talks focused on the responsibility of founders, why young kids are leaving online platforms, and how to build tech that “works for us.” These conversations, punctuated by moments of AI comedy from Laugh GPT (an AI bot which attempts to do bits with real comedians), a graffiti-painting area, and a free library full of books to inspire founders and developers, all pointed to the tech elite’s current obsession with AI.

The worry on the event hosts’ minds was how we may regulate AI in order to slow down its progress, and build guardrails to protect everyday users. Yet I didn’t hear a single concrete plan or see any policy wonks on stage. The plastic turf was mostly filled with tech workers, founders, VCs, and outreach coordinators. It was a Tech Week event, after all. What AI regulations were needed, and why, remained a mystery.

However, for Roy Bahat, CEO of Bloomberg Beta, we don’t necessarily need regulations but rather responsible tech founders in order to defeat the other evil founders of the world. I’ll let him explain.

“This is the evil twin problem. You start a company and you want to do the right thing about everything. But somebody else starts the exact same company, only every time you make the responsible choice, they make the evil choice,” Bahat said. “If they win, it does not matter that you are responsible because you don't exist now. And so the question is, how can you both be responsible and exist? And that often requires some victory in a competitive market.”

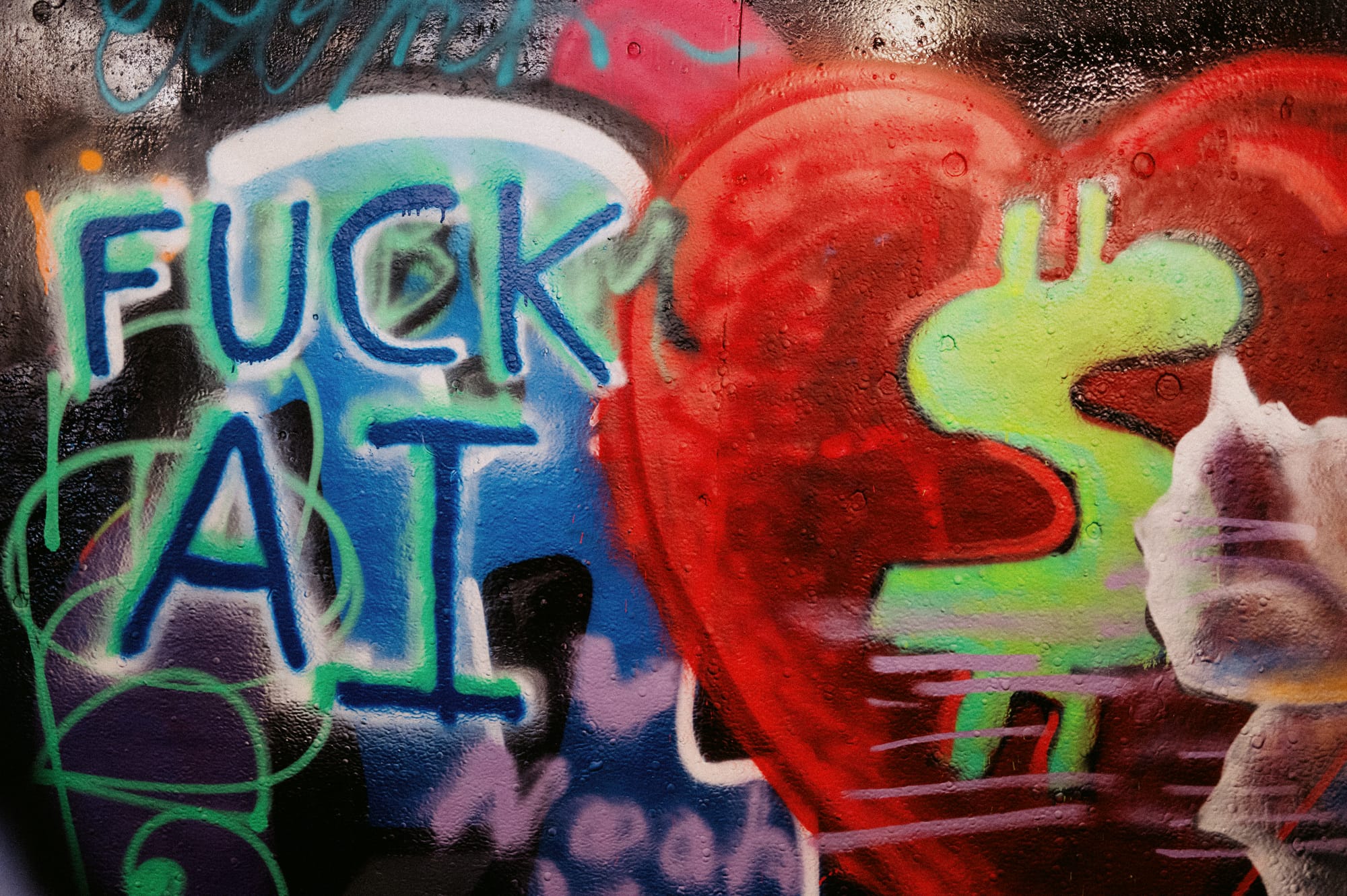

People seemed genuinely in awe of this rationale. No one in the audience questioned Bahat’s logic during the Q&A, yet I stood in the back with too many questions myself. What if you aren’t as brilliant as the evil twin? What if your evil twin isn’t evil, and what if evil twins don’t exist? Who decides what constitutes “evil” in this situation? And, why do we need to compete in a market to make something valuable for humanity? It’s the kind of thing that frustrates me most about the dominant voices in the tech industry: they seem convinced that they are the only people to have had a thought. From this perspective it seems that questions from outside the tech industry, such as if AI is really worth the billions they allege, are not, then, to be taken seriously. As the talk and Q&A ended, I walked past the graffiti room, watching a tech worker paint a dollar sign, then outline it in a heart.

I like to look at things from a distance, get to know their outlines, like looking at a lake from a hill. Here, however, I was in the lake, and it was murky and I was lost and there was little I could really do about it. I started to lose sight of the point of this event. The words spoken around me became more and more meaningless as I wandered around the turf. Was AI actually worth the hype? The voices around me, mostly, said yes. Was it going to take my writing jobs? Would it take my barista job too? No one seemed to know.

With little proof these chatbots have made our work or our lives better, those at this event, and other events like it, seemed convinced that AI chatbots are the future, and that there is no alternative.

Now as I write this I realize that I was just trapped within an event that was itself another gear within the tech industry’s great hype machine. And it really is just hype. Companies like Klarna are rehiring their customer support employees. Others are worried about the sycophancy of these large language models, chatbots such as ChatGPT, and the dangers they pose for people’s mental health, with “AI psychosis” already being widely talked about. Even today, analysts are trying to understand if there is an AI bubble, and if it is soon to burst, and just how much money these companies will lose. And yet, with little proof these chatbots have made our work or our lives better, those at this event, and other events like it, seemed convinced that AI chatbots are the future, and that there is no alternative.

However, even leading AI companies themselves keep finding evidence that these models don’t work as advertised. Anthropic just released a paper detailing how even a tiny amount of faulty data in a large language model may compromise the entire system, meaning these systems might never be so trustworthy as to fork over to them the keys to our society — something the tech industry seems so desperate to do. What are the tech bros going to do once that sinks in?

I am a barista and a writer. I usually write about ecology, explaining dynamic ecosystems to audiences. So, I don’t see the tech world from the inside but rather from the hill, looking down on the lake. Maybe I only know basic CSS and HTML, but I know enough to notice that many in this industry have lost the forest for the trees. To them the world — the mountains, the oceans, our bodies and their propensity toward death, are simply failings of the natural system. What’s more, the potential harm to ecosystems for large data centers, and AI models’ increasing contributions to an ever warming climate don’t seem to be a concern for this cohort of people. AI is all that matters. Only in technology, in AI, will we find order and eternity. However, they don’t see that many of us do not co-sign this world they are attempting to create for us.

Later in the evening onlookers watched as Laugh GPT failed to do bits with real comedians. A comic, at a point, berated the audience by saying they “single-handedly ruined San Francisco” and called these tech workers “terrible humans.”

Arriving home that night, I opened the contents of a little folder I picked up at the free library as I left the event (I also picked up a copy of Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Parable of the Sower). Inside was a pack of stickers with which to play out moral thought experiments at your workplace — presumably a tech company. One of them read “Slow Down Ask Questions” written over Meta’s adage “Move Fast and Break Things.” Many people at this event did seem to want to ensure the new world they were building was a good and just one — to “not be evil” as Google once put it. I think that desire, genuinely, is great, though incredibly vague.

As the Omidyar Network would have it, this just future is made through regulation. Maybe those at the block party do want regulations, but only as a kind of god stepping in to stop them from following their worst compulsions. But regulations, written by those in tech, won’t do much to stop the lucrative incentives at the core of the industry. Tech is full of modern-day robber barons who have made unprecedented amounts of wealth from the lack of regulations. And while it is admirable to see some workers, and some founders, come together to advocate for regulations, there is little chance that any true change will come from within the industry. Change, inevitably, will arrive from outside its bubble.