AFTER SCHOOL: Strike is Over — For Now

Teachers will now decide if they'll accept the contract. Learn about the process, and what could come next.

For more than 40 years, the Veterans Hall has modeled what a shared public space can look like for those cast off by society. Can it withstand increased privatization?

It’s July 26th, 1984 and you’re on your way to the free “Rock Against Reagan” show being thrown at the Santa Cruz Vets Hall. Someone published a letter in the June 1984 issue of Maximum Rocknroll writing that punks had been present at all kinds of demonstrations in San Francisco recently, ranging “from anti-nuke and anti-Reagan Administration to animal rights and tenant rights rallies,” so much so that “even ‘straight’ media” had taken notice. And just a few days ago, on July 19, 1984, a Rock Against Reagan-Racism show was thrown outside the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, and nearly 300 punks were arrested by police for refusing to disperse while chanting “No War! No KKK! No Fascist USA!”

That same night in July 1984, you’re just 60 miles south of San Francisco and you might see some of those punks recently released from police custody. They’ll be there for their second Rock Against Reagan show that week. Holy Sisters of the Gaga Dada and Delusions — two local Santa Cruz bands — are on the bill. Bay Area acts X-Tal, Atrocity, and Trial have come down to play the show. And two touring New York bands, Reagan Youth and Moja Nya, are performing. In a handwritten font above the band names on the flyer, it says “Govern our own mentality.” The show’s running from 4 to 11 p.m. at 846 Front Street, and you’ll be there, packed into the Veterans Hall auditorium with around 700 other punks raging against Reagan remaining in office for a second term.

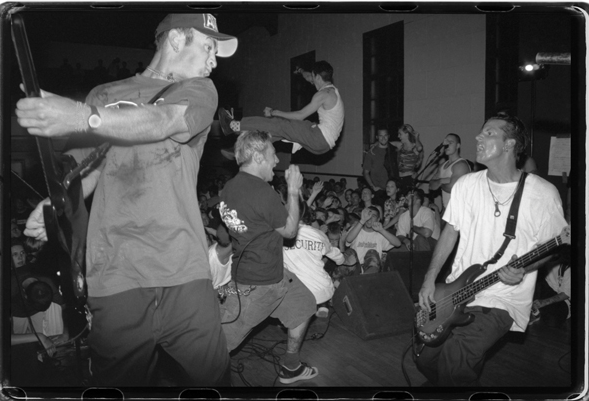

Forty-one years after that show, the Santa Cruz Vets Hall is still a site of political punk. While there aren’t any ‘Rock Against Trump’ shows being thrown today that rival those of the Reagan era, bands that have called the Vets Hall home for years are speaking out against the Trump regime at their 2025 gigs. Bands like Santa Cruz-based Good Riddance, or Rise Against, who played the Vets Hall for the first time in 2001, and chose to perform there again and again while on tour — even after they eclipsed a level of fame that exceeds the venue’s size — have gone on the record to speak out against the rise of fascism in the U.S. “The Vets Hall was our spot, and it was a lot of bands’ spot,” Chuck Platt, bassist from Good Riddance, told me.

The Veterans Memorial Building, as it’s formally called, opened in 1932 after Santa Cruz County voted to establish the space to serve local veterans, but since then, it’s done so much more. I spoke with band members, show promoters, and current and former Vets Hall workers, and asked them how the Veterans Hall became so intertwined with the Bay Area punk and hardcore communities. They told me the story of how Santa Cruz veteran communities opened their doors to punks, many of whom aren’t shy about screaming anti-establishment sentiments into a microphone. The politics of the Santa Cruz Vets Hall are much wider than what’s written in the lyrics of the bands that perform there, or the comments that band members make on- and off-stage.

Above all else, the politics of the Vets Hall come from the fact that for the last 40 years the space has served poor and working class people — veterans and punks alike — who needed somewhere to call home.

Dave Ramos, who served as a medic in the Iraq War and is the current managing director of the Vets Hall, said that across the country veterans face two serious issues: housing insecurity and difficulty finding access to consistent work. In Santa Cruz county, which was named the most expensive place to rent in the U.S. for the third consecutive year according to a recent report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), these challenges are more acute. As reported by the NLIHC, you’d need to earn $81.21 per hour to be able to afford a typical two-bedroom apartment in Santa Cruz.

According to Ramos, the Vets Hall aims to remedy this situation by offering services to veterans like low-income housing vouchers, employment support, and a Veteran Affairs (VA) medical team. These programs align with the Vets Hall’s original mission to serve the county’s veterans. That mission has been reinforced over the years as parts of the building have been designated for veteran-use only. But even so, the building offers services to civilians that are critical to keeping members of the Santa Cruz community alive and well, like Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and spaces for DIY artists and musicians to gather.

“DIY is something that’s done out of necessity,” said Bailey Lupo, who plays bass in San Jose and Santa Cruz hardcore band SCOWL. “A lot of us are working-class, we don’t come from money…but when it comes to finding people that want to be in bands and create art to any degree, you’re going to make it work. Even if it doesn’t sound or look punk, it’s inherently punk as fuck.”

Bay Area punks have flocked to the Vets Hall for more than 40 years to see local and touring bands, get sweaty in the mosh pit, and crowd surf for their first or hundredth time. But most probably don't realize the extent to which they’re reaping the benefits of the unique historical circumstance embodied in the Vets Hall, where there’s an unlikely symbiotic relationship between those who fought for this country and those who have fought against it. The DIY culture and leftist politics espoused by the punks who play and attend Vets Hall shows can’t be separated from the Veteran Memorial Building’s overarching mission to support local veterans.

“The people that run the building understand that allowing these events to happen there is what allows this building to stay open,” Joel Haston, who worked at the Vets Hall for two and a half years and promoted shows there, explained. “The veterans like that...people feel like they can come into the building and express themselves however they want. The veterans love that this is a home not just for [them], but for other people as well.”

Vets and punks often pass each other like ghosts in the building, barely leaving traces of each others’ presence. The punks have helped keep the lights on by renting out the Hall for shows, and the vets have given the punks a room of their own since the 1980s. But even if they rarely or never come into direct contact with veterans, all musicians, promoters, and concert-goers I spoke with expressed a commitment to keeping the space as they found it the first time they walked in.

“These are sacred spaces for a lot of people,” Lupo said. “Don’t do anything that could be perceived as sketchy or illegal even, which could ruin the spot, get the cops called, or get them written up for violations. Whether it’s a house show or Gilman or the Vets Hall, it’s very easy for local governments to close these venues down for any reason they feel like.”

It seems unlikely, though, that punks’ respect for the Vets Hall over the years has been an explicit act of solidarity with veterans. It’s more that when you stumble upon a great space to throw shows, you don't push your luck.

And in fact, punks got a taste of what it would be like to lose the Vets Hall as a venue for 10 years, when the Vets Hall closed to the punk community from 2010-2020. Despite some allegations that bad behavior at punk shows shut the venue’s doors, in reality, the Vets Hall closed at the County’s insistence from 2010-2014 to repair long-standing damage from the 1989 Loma Prima earthquake, an order which some veterans disagreed with.

While the Vets Hall re-opened to veterans in 2014, concerts were put on hold as a result of disagreements between the building’s stakeholders, which includes veterans themselves, the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) organization, the board of trustees, the city, and the county — none of whom seem to agree about who has jurisdiction over the building in the event of an emergency or how to keep the building well-funded. It should be that the county, which owns the building, funds the space; but the county is only one entity that supports building operations, maintenance, and programming. Without enough public funding, the Vets Hall also relies on private events, including concerts, to keep the doors open to vets. This was ultimately one of the reasons the Vets Hall reopened its doors to the punk community in 2020 when Chris Cottingham took over as director. Cottingham and Ramos, who has taken over as director more recently since Cottingham left, both view live music — or at least the funding it brings into the space — as a way to honor the veteran-centric mission.

But the shows that made the Vets Hall a prime punk venue and DIY community space between the ‘80s and the early aughts looked a little different when they began again in 2020. The basement, or the “bunker” as many veterans refer to it, had been a prime location for punk shows from the ‘80s to the early 2000s. “The basement shows were the best,” Platt said of the ‘90s shows. “It was more of a punk vibe. I would say the basement held like 200 people maybe. And it was always completely packed.”

The basement was a part of the building demarcated as civilian-free in a 1990 ruling by a local Santa Cruz judge. Despite his ruling, it was still used for hardcore shows for over a decade. Veterans didn’t seem to mind that the basement was used, as long as the space was handled with respect and care; and allowing promoters to continue booking shows in the basement kept the punks, who felt most at home there, coming back.

In the 10 years that the Vets Hall wasn’t throwing shows, the basement changed tremendously. “That area that’s veteran-specific is now very veteran specific, and it’s been isolated, so there’s no access" Ramos said. “We also run a food pantry every week […] We have a kitchen that’s being used seven days a week pumping out 270 meals a day feeding the homeless shelter up the hill. It’s constantly being used. So the use of the basement in particular for punk rock shows, I’m not a fan of doing that. The auditorium is perfect and beautiful. And even if the show is a lot smaller and would be basement sized, we have a room upstairs… and it has a sound system.”

The auditorium may be beautiful, but it’s not always perfect for a punk show. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, looser security measures allowed promoters to pack the auditorium. “Let’s say the capacity was 400 people,” Platt remembered, “I think the biggest show I’ve ever seen there was probably 750 people. It was wild…. It was a legit pit, and then like packed to the back. And the [mezzanine], packed. It was way different. And it was like $5 to get in.”

Now, for some of the shows in the bigger space, ticket prices tend to linger around $30-40, a price tag that’s too steep for a lot of punks. The increased ticket cost comes at the expense of making sure the venue can stay open, which requires that promoters adhere to what Haston described as an outdated insurance policy and operating permit. For example, the Vets Hall’s policy requires that at all shows, one security guard is hired for every 50 people in attendance — double the security you’d find at a standard venue like the Catalyst Club, according to Haston. Because of this, Haston said, it’s more expensive to throw shows at the Vets Hall, and concert-goers bear the brunt of that cost. And the DIY vibe that punk shows used to have at the Vets Hall has also been a casualty of these changes.

“For some reason I just liked the basement shows better,” Mark Guerrero — who’s played in a number of local bands including Make It Count, Dukes Up, P+, LOCKJAW, and A Life Spent — explained. “I remember hearing Dangers say ‘No stage is the only stage for me,’ and I was like, somebody who put it into words! Because when you have a stage, it almost puts you on a pedestal and I don’t like that at all.”

Guerrero frequently attended and performed at the shows that musician and punk show promoter Spencer Biddiscombe threw, many of which were in the Vets Hall basement among other DIY venues including houseshow spaces in Santa Cruz, Watsonville, and Salinas. Biddiscombe has always been revered in the community, partly because he prioritized people in bands and the local scene over making a profit from the shows he threw.

“We made sure bands always got paid,” Biddiscombe said. “Bands were often getting paid more than what their guarantee would be…instead of their $500 guarantee, they might walk away with $1000 because 300 people showed up and I wasn’t a promoter that was booking shows as a business. It was always because I wanted to see the bands that I wanted to see, or my friends wanted to see, or that people were interested in.”

Throwing shows in this way that prioritized paying touring bands that the Santa Cruz community truly wanted to see is less possible now, according to Biddiscombe. The houseshow scene has been deflated since laws were put in place to benefit Santa Cruz’s landlord class. One ordinance from 2005 that is still in place notifies the landlord when there’s a noise complaint at their property, taking autonomy away from tenants. This had a profound effect on the DIY punk houseshow scene, according to Biddiscombe.

“Santa Cruz kind of got crushed because nobody wanted to get kicked out of their house,” Biddiscombe said. But he was also optimistic about the Santa Cruz scene. “People here have always found a way to find spots to make shows happen.”

Punks are still finding a way, but like their veteran counterparts, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to live in a place as hostile to poor people as Santa Cruz — let alone to produce art and facilitate a DIY culture without a space of one’s own. While the Vets Hall has long been a beacon of solidarity between punks and vets in the Santa Cruz area, the direction that shows at the Vets Hall are veering into is representative of a larger pattern of public and DIY spaces becoming privatized.

But digging into the history of the 93-year-old Veterans Memorial Building provides a model for how we might fight against this privatization. The Vets Hall holds a legacy of political punk, of veteran-rebels organizing against U.S. intervention in Nicaragua, and of social programs offered to veterans weekly that might serve as a precedent for the kind of governmental aid all people deserve. Honoring that legacy is more needed than ever. If shows are getting more expensive and less accessible to the punk community, it’s only a sign that punks and veterans should join forces to demand more funding from the city and county for the Vets Hall, which they’ve both called home.