Highwire Coffee Roasters’ Union Says Management Stalling On First Contract

Management has also hired an infamous anti-union law firm

University cuts make headlines. But what happens to lecturers after they lose their jobs?

“It really was a funeral. [...] I didn't have any expectation that my job was going to be saved.”

Jennifer Beach was one of 155 San Francisco State University (SFSU) lecturers metaphorically put to rest on December 11, 2024, a mild afternoon during the last week of class for that fall semester, by a group of faculty, students, and staff.

After over a year of protests and lobbying, they were unceremoniously “exited” by the university administration in classic human resources speak. Instead, with a coffin they had borrowed from the School of Theatre & Dance hoisted onto their shoulders and an ad hoc group of faculty brass musicians playing New Orleans-style jazz in tow, their colleagues and comrades held a funeral procession to mournfully, yet affirmingly honor the dead.

“We are gathered here today to mourn the loss of an unknown number of our lecturer faculty,” read Ryan Moore, a lecturer in Sociology. “The administration's official explanation, the cause of death, is that there's been a decline in student enrollment.”

Moore eulogized not only his fired colleagues, but also public higher education. “The admin is also now in the process of executing another murder, so there is another thing to mourn here today, that is the death of higher education as a public good, higher education as something everyone deserves access to.”

Universities have long treated adjunct faculty as disposable. When they announce budget cuts, it usually means lecturers are about to lose their jobs. Yet, just because the university has left them for dead does not mean we have to.

Seven months after a round of firings at SFSU, Bay Area Current checks in on the lives and livelihoods of laid-off faculty.

At death’s door

The funeral, organized by faculty and students to honor the laid-off contingent faculty, was the last of a series of strikes and other actions that ultimately couldn’t sway the university’s president Lynn Mahoney and other administrators from downsizing the university’s workforce.

President Mahoney has slashed course offerings and implemented several rounds of layoff over the last two years, often gutting entire programs that depend on the labor of lecturers. The university blames the cuts on a drastic decline in enrollment, which has dropped from around 30,000 students in 2015 to just over 22,000 in 2024.

Beach, who earned both her undergraduate and master’s degrees from SF State, had taught in the Writing Program since 2005. Almost all of its contingent lecturing faculty — those like Beach teaching fewer than 15 weighted teaching units (WTU), roughly equivalent to 5 courses — were laid off in the fall, leaving the program unrecognizable. The funeral marked an end to Beach’s nearly 40 year relationship with SFSU.

“There's nothing left there. Forty years of my life at SF State. It was like my small town. That's where I met my first girlfriend. My small town. But then at a certain point you have to move on,” Beach said. “And when you get a bird's eye view, you see that it's happening to education across the board.”

Births, deaths and how we got here

Decades of disinvestment from public education and, particularly, from the humanities, means small, student-centered composition classes like those offered in the Writing Program have become a rarity. At SFSU, which serves a diverse, working-class student population, the impacts are profound. Since 2023, lecturers have fought to preserve not only their own jobs and livelihoods, but also the high quality education they offer to students.

“I had a little, tiny hope that they would keep a few people in the writing program,” Beach said. “I met with the provost and I said, you're making a bet that your decades of investment into our kind of specialized pedagogy and training and collaboration, meeting this very complicated set of student needs was all a waste and you don't need it. And you might be right. Maybe the Shakespeare professors can do the same thing that we did, even though they don't have any of the training or resources. But you might be wrong. And if you are wrong you have no one left.”

The administration points to demographic decline — birth declines in the early 2000s mean fewer 18-year-olds have been enrolling — as a justification for downsizing. However, the cuts don’t match the declines in enrollment.

“If they lost a third or a quarter of their students,” Beach said, “they would've laid off a quarter of their faculty in the writing program. Instead they laid off everybody.”

Fellow former Writing Program lecturer Christy Shick — who had taught at SFSU since 2012 — echoed Beach’s dismay at how the university had chosen to sacrifice not only some of its most dedicated educators and their decades of institutional and pedagogical knowledge, but also the education of its students.

“I didn't see the enrollment decline as being so dramatic as they said,” Shick said. “Meanwhile they're raising the classroom caps to pack more students in classrooms, getting rid of second semester writing requirements, and getting rid of general education requirements to make it easier to graduate.”

As students watch the quality of their education go down, and the price of tuition go up — the California State University (CSU) board of trustees approved a 6% increase annually over the next five years — it’s no wonder that they are pursuing other options like community college transfer, the UC system, or forgoing higher education altogether. “Right now, for most SF State students, somebody works a second job for all of my students to go to college. Often that is the student themselves,” Beach noted.

Fighting back

Universities are increasingly managed like business, and they’ve been at the vanguard of the gig economy, to the detriment of students and faculty alike.

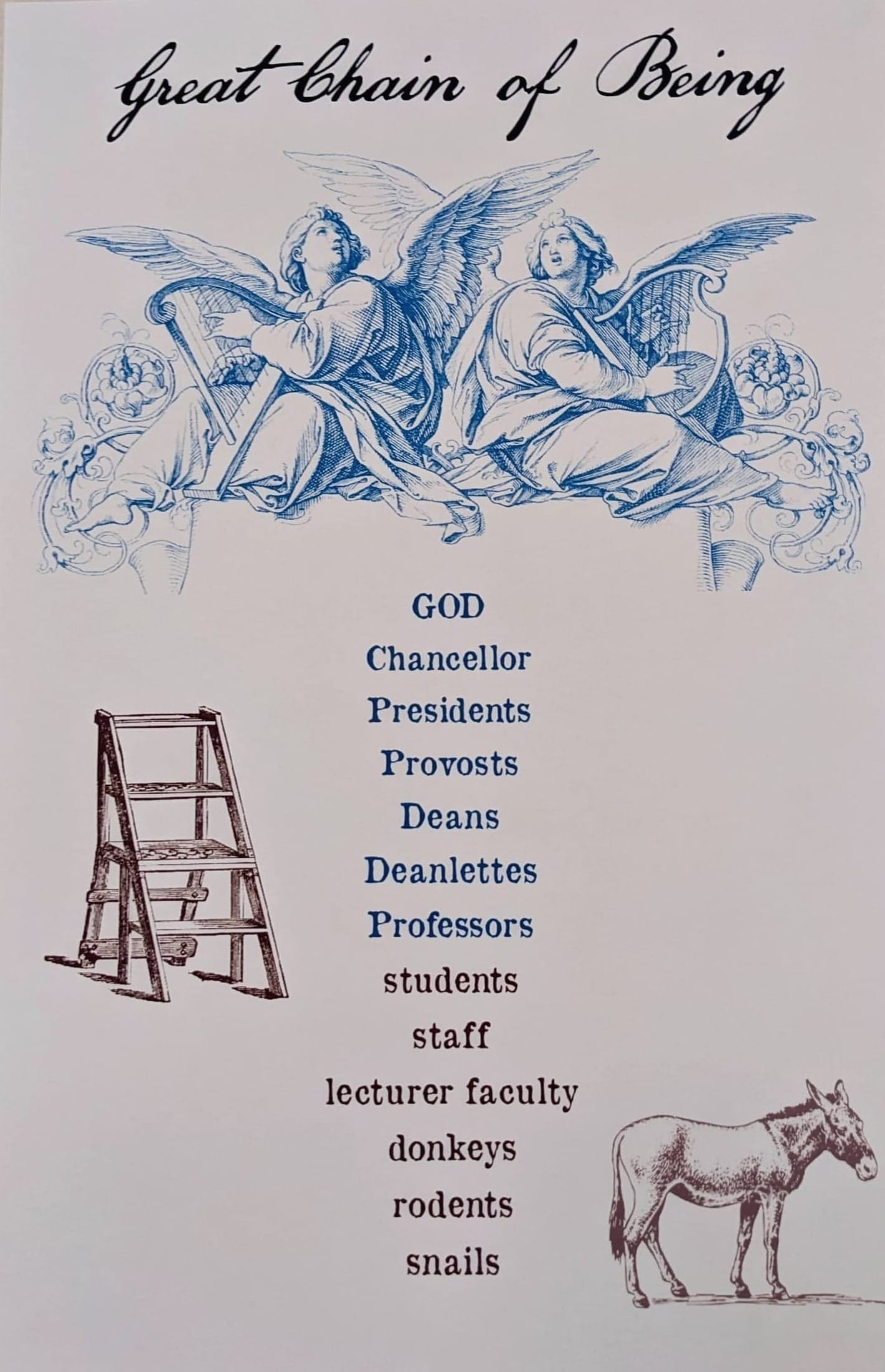

“Adjunctification” has transformed faculty positions that once guaranteed benefits, job security, and academic freedom into part-time lectureships on a yearly, semesterly, or even per course basis. In the 1970s, 75% of courses were taught by tenure-track professors; now 75% are taught by contingent faculty, many of whom hold PhDs, MFAs and other advanced degrees in their field just like their tenure-track colleagues.

Whether they get called lecturers or instructors—but god forbid professors!—they often teach the “front-line” general education classes in writing, languages, and introductory sciences and math.

“It worked out really well for me over the course of 17 years,” said Sean Connelly, one of several lecturers in the Department of Humanities and Comparative World Literature that was also laid off. “We all know on some level as an adjunct that you're kind of disposable. You’re an at-will hire. You have some protections but push comes to shove, if they don't have classes, you’re not gonna get the work.”

In 2023, stalled contract negotiations coupled with administration’s calls for layoffs and tuition hikes spurred a year and a half of organizing. “I found out I was going to lose my job and it really lit a fire. I wanted to do something before I left," recalled Connelly.

“The year before we fought like hell against the cuts,”said Brad Erickson, SFSU chapter president of the California Faculty Association (CFA) and lecturer in the School of Humanities and Liberal Studies. “We had three major on-campus rallies with faculty and students. We organized so hard.[...]. We couldn't have done better and yet we didn't save jobs. The other thing that happened was our union leadership called off the strike without consulting the members.”

For Erickson, the lack of material success discouraged those who remained, while the layoffs got rid of “a lot of the people who were the best at organizing.”

The abrupt firing left Connelly without a political home. “You’re not just losing your job. You're losing the thing that defined you. Your work life. That's really crushing. And you’re losing even just your opportunity to be a participant.”

While full-time lecturers have had their jobs spared for the time being, achieving full-time status was rarely a transparent process. Indeed, they comprise only 6% of the lecturing faculty according to Erickson. Beach was told it was nearly impossible (which the numbers all but confirm). Connelly had the impression that he may have been able to get it if he had only asked the right person at the right time.

However, with fewer and fewer classes offered each semester, many lecturers fired in the fall weren’t teaching enough units to be eligible for benefits after the mass layoff.

“They whittled me down to one class. I lost health insurance. And then they let me go,” Connelly said.

“They whittled me down to one class. I lost health insurance. And then they let me go,” Connelly said.

Through the CFA-bargained contract, lecturers must teach six teaching units (approximately two courses) to secure benefits like healthcare. This made sense 40 years ago when lecturers were primarily professionals teaching one-off classes in their areas of expertise. It no longer makes sense now that universities depend on lecturer labor and exploit lecturers' dependence on cobbling together enough courses to make a living, often at multiple universities.

Shick was left with a shadow of the pension that she had imagined after over a decade at SFSU.

“I lost my pension,” Shick said. “I had just reached [early retirement age] and I was able to keep my benefits, which isn't nothing, and collect a pension of, I don’t know, $600 bucks. But if I had kept working [at my expected course load] there another 12 or 13 years, I would've retired with a decent pension that I could live on.”

Strength through solidarity

When the university did not offer any support to laid-off staff, it fell on faculty, both ladder — those on or through the tenure process — and contingent, to offer solidarity and guidance. According to Connelly, Maricel Santos, chair of the Department of English Language and Literature (which houses the Writing Program), and others, put together a two-day event in the fall offering career and retirement advice.

“People could try to find out about retirement, which is really byzantine,” Connelly said. “For those looking for new work. The kinds of jobs that are out there. Do you wanna teach K-12? Do you want to go to a private high school?"

For Connelly, the administration’s callousness really showed in their failure to consider these practical matters. “There were all of these practical considerations that for Mahoney and others, they just didn't even occur to them. What if there is a job opening? How will you get in touch with [laid-off lecturers] if you don't have their email accounts?”

Rallying against adjunctification has been Erickson’s intellectual and political life’s work. “I've been teaching here for ten years. I've taught in eight departments at five universities.[...]. I've been stuck in this purgatory of the two-tier system which is something I have struggled against consistently in my scholarship.” Erickson has published a peer-reviewed book chapter titled “Abolish the Lecturer: A Manifesto for Faculty Equity.”

Though Erickson is still at SF State, the prospect of Governor Gavin Newsom’s $375 million dollar budget cut to the California State University System (CSU) is looming. He fears there will be even more layoffs in the fall.

“Our president [Mahoney] has told us that if the governor’s planned cuts to the CSU go through that there would be about 100 layoffs in the fall, including tenure line faculty,” he said.

The university would have to go through the same process to lay off Erickson, a full-timer, as it does with tenured faculty. Nevertheless, due to the two-tiered system, faculty are entitled to courses before their lecturing colleagues.

“About a month ago I was told that I had no courses for the fall. In fact, I'm still not officially on the schedule.” A week later, Erickson was then told by the chair of Liberal Studies, Jose Acacio de Barros, that he would be teaching writing in the English department. Attempting to secure Erickson's employment in the face of the chaotic whims of the university, Barros later told him that he would be teaching forest ecology.

“Now I know what I'm doing this summer: Learning a new discipline!” A week later, Erickson said that Barros told him that he would be teaching international relations instead and could adapt a course he's already taught. “I can't say no to any of these things in the fall,” he explained, “Because if you say no, you've turned down work, and then if you've turned down work, that's it.”

Barros did not reply to a request for comment on Erickson's teaching schedule.

For Erickson, the gutting of departments and the subsequent shuffling of faculty within and across fields results in a “trickle down of harm.”

“[It] really is dehumanizing because it makes you feel like you're just a product on the shelf and you’re interchangeable."

“[It] really is dehumanizing because it makes you feel like you're just a product on the shelf and you’re interchangeable,” he said. “Nevermind however many decades of experience and your expertise. I'm just fighting for agency for me and all faculty right now. Because the ladder faculty are also getting treated like this.”

STEM: The next frontier of cuts

The disregard of disciplinary expertise and the shuttering of programs is not limited to the humanities.

Malori Redman arrived at SF State in 2009 as an undergraduate to study atmospheric and oceanic science — a degree that no longer exists.

In fact, Redman, a lecturer in what is now the School of the Environment History, started teaching at SFSU in 2018 after the university failed to fill vacant tenure-line positions in the Department of Earth & Climate Sciences.

Facing falling enrollment, the Department of Earth and Climate Sciences began the process of merging with the Department of Geography and Environment and the Environmental Studies Program in 2022 and the School of the Environment officially formed in 2023.

“We need to boost our programs because by ourselves we're all tiny and we're not going to survive but maybe together we can survive through all of these massive budget cuts and targets on our backs for having low graduation rates,” Redman said.

But with the university offering the school fewer courses and thus fewer teaching units, Redman feels “we're getting our knees knocked out from under us before we can stand up.”

Lecturers in Redman’s department have been able to stave off layoffs and precarity largely through solidarity. They’ve worked internally to ensure colleagues meet the minimum requirement of six teaching units in order to qualify for benefits.

“I have colleagues whose classes did not meet that minimum of six. So they lost their healthcare for a semester or a year and that was really detrimental,” Redman said. “They had surgeries scheduled and then they had to cancel them. And even right now we're pulling strings to make sure some of these lecturing faculty have that 6 unit minimum.” Like many adjuncts, Redman works more than one job, supplementing her courses at SFSU with teaching in the San Mateo Community College District.

Life after death

Connelly is currently unemployed and actively looking for work. He hopes to teach at Diablo State Community College in the fall.

For her part, Shick is still appealing for faculty emerita status from SF State, an honorary title that would allow her to maintain an affiliation with the university. “I contributed a lot of unpaid hours to the university. And when you're laid off you lose your email accounts, your library access, Zoom. I don’t know how many job applications are on that email.” Waiting to hear back, she drove down to visit friends in Mexico and finish her first novel.

And Beach, who does some part-time work at local non-profit Prison Radio, is retraining.

“Fifty-eight [years old] is a very hard time to be laid off; I'm not quite in a place where I want to get a Master’s in Library Science and launch a new library career.” Instead, Beach is taking a few courses in digital asset management at San Jose State and plans to begin applying to teaching, library, and non-profit positions in August.

Despite all of the hand-wringing about demographic decline and the need to downsize, administrative bloat remains untouched. President Mahoney’s salary is $472,857, and her housing allowance of $60,000 is well over what most contingent lecturers make.

Despite all of the hand-wringing about demographic decline and the need to downsize, administrative bloat remains untouched. President Mahoney’s salary is $472,857.

As Erickson has long argued: “The austerity is artificial.”

“The fact is that the highest echelons of admin,” Connelly noted, “may as well be working at Meta. Their value system is not even in line with the missions on some level. If the mission still exists. I think it exists with the rank and file.”

In addition to high executive compensation, the CSU system has a nearly $2.4 billion reserve; however, according to the Chancellor’s Office only $777 million is uncommitted. The CSU system also maintains a $7 billion investment portfolio.

Looking forward

SFSU is not alone in its budget struggles. Sonoma State has announced plans to shutter a number of academic programs and its entire athletics program. Similarly, Cal State East Bay faces a $20 million shortfall. The CSU Board of Trustees has even proposed merging the three schools’ administrative and finance services.

“Now we are seeing it happen to the whole country,” Shick said. “Top down heavy cuts. No transparency. No conversations with anyone. Not even looking at what they're cutting.”

For Erickon and the 29,000 lecturers, professors, librarians and coaches the CFA represents, the fight continues. Workers throughout both the CSU and the UC systems mobilized throughout the spring to thwart proposed cuts of 8% in the state budget.

While the eleventh-hour budget signed by Gov. Newsom on June 28 largely spared higher education, accounting tricks will defer the 5% increase Newsom pledged to both systems in 2022 until 2028. Sonoma State will also receive a one-time infusion of $45 million to help reduce its deficit, though it is unlikely their sports programs will be restored this coming academic year. Ultimately, the budget does nothing to address federal cuts to higher education, with both systems currently implementing a hiring freeze due to ongoing fiscal uncertainty.

All laid-off SFSU lecturers interviewed by the Current remain deeply committed to public higher education, even if they have been forced to find other work. As Beach said, the struggle for higher education has to itself be an ongoing, living thing.

“I am some kind of Marxist. I do believe that people do have to, by the nature of humanity, respond to bad conditions by resisting,” she said. “I do think that will happen and it's very difficult to know exactly what's going to make social change happen.[...] But I think people have to demand high quality public education and they have to do it all the time.”