Bay Area Chinese Leftists Are Making Language Political

We were in a very Chinese time in our lives. We decided to do something about it.

We were in a very Chinese time in our lives. We decided to do something about it.

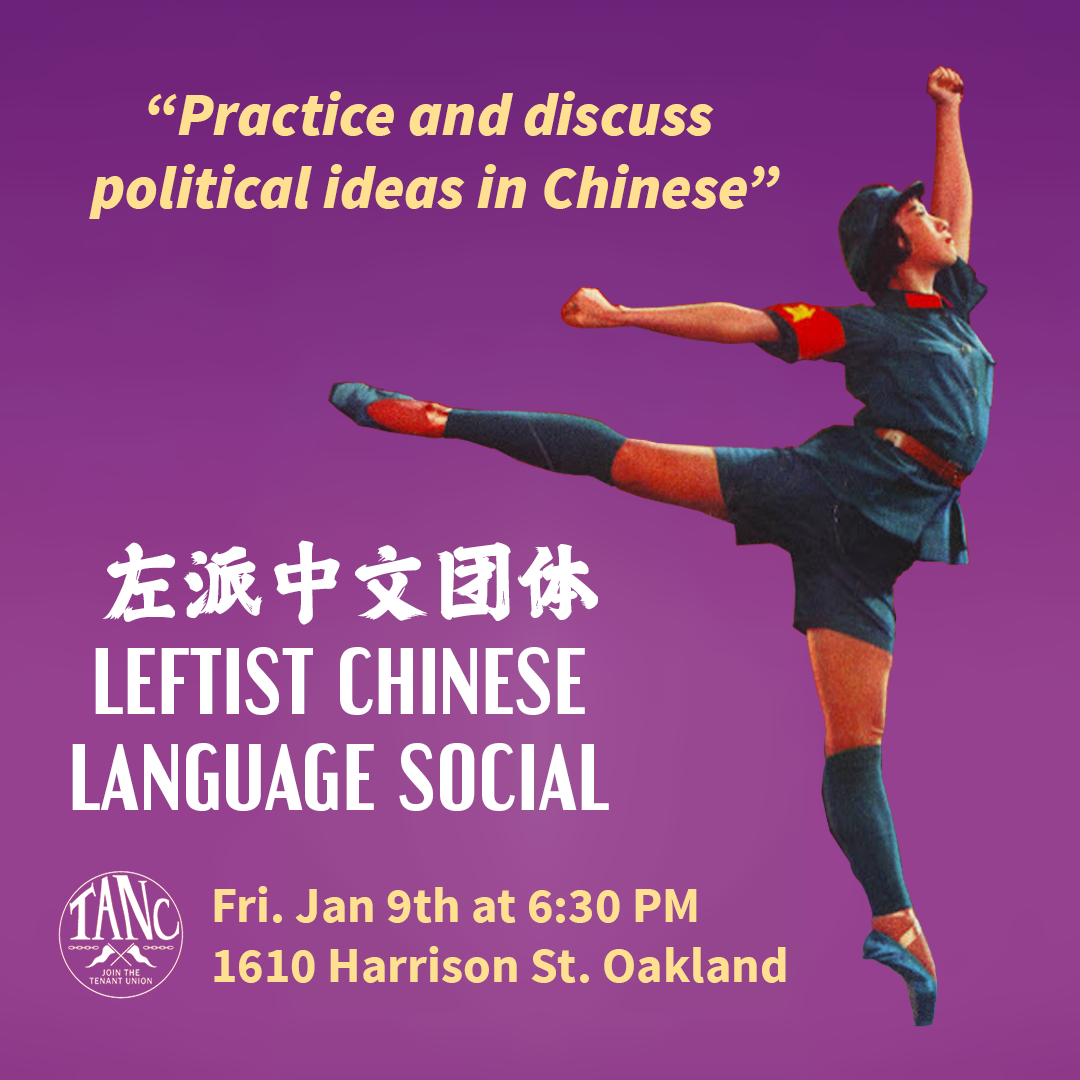

Building community is a constant struggle in political organizing. Building language capacity to reach immigrant communities is another. For over two years we — along with dozens of other Chinese-speaking organizers in the Bay Area — have tackled both these challenges through monthly language socials that bring together Chinese speakers who share a leftist political orientation.

After one of us returned from a trip to Taiwan and China in 2023, we — Tim Tia and Yuzhuan Hong — noticed that despite the density of Chinese and Chinese Americans, the Bay was surprisingly lacking in two types of spaces: first, opportunities to practice Chinese language in a casual community setting; and second, explicitly political spaces for Chinese and Chinese-speaking organizers.

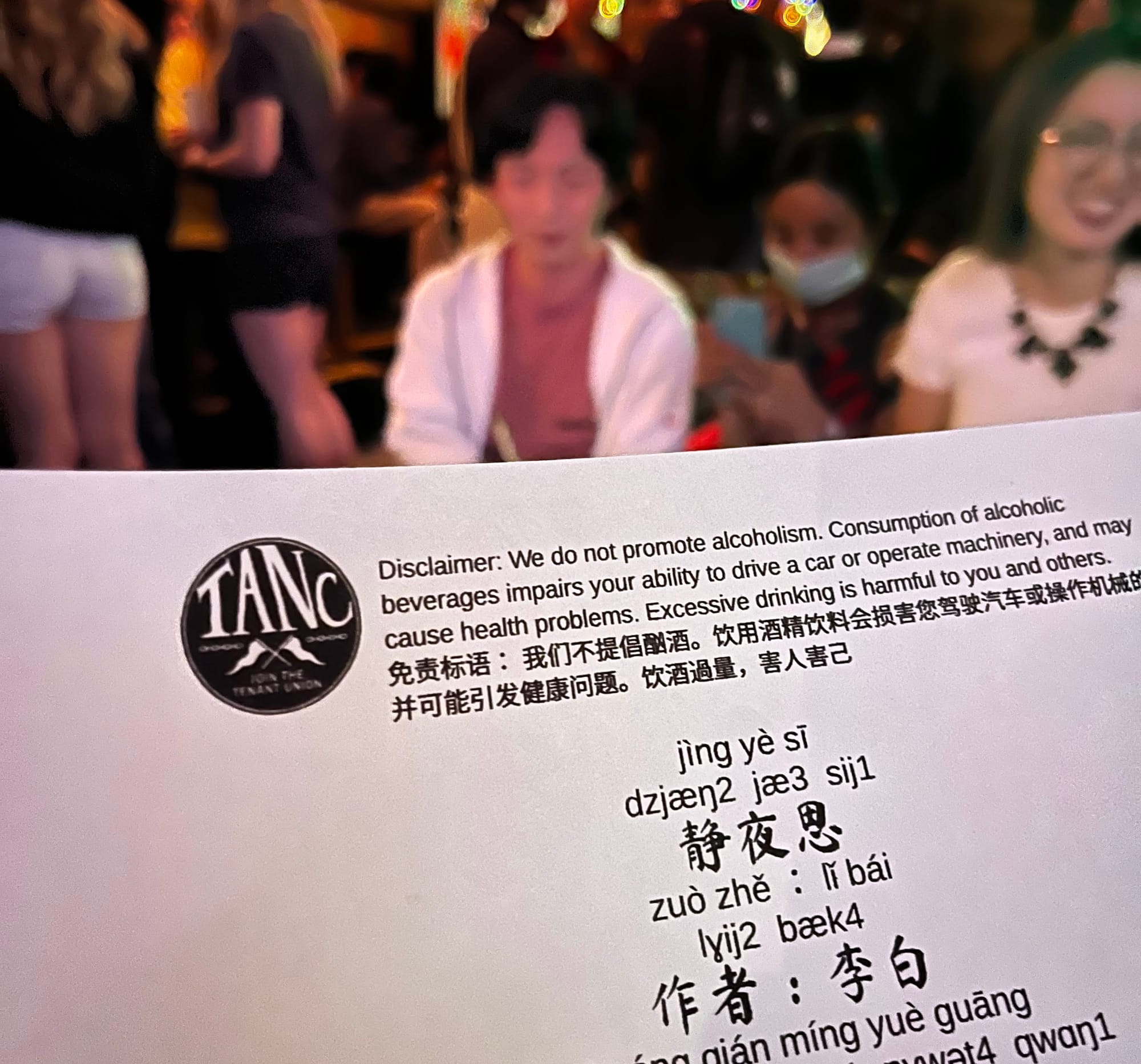

That’s why, in October of 2023, the two of us brought together friends and comrades at Li Po Cocktail Lounge in San Francisco Chinatown for the first of what would become a series of leftist Chinese language socials. The dozen or so attendees struggled to hold our political conversations in Chinese as they hopped from Li Po to Lion’s Den, Moongate Lounge and Yeut Lee Seafood Restaurant. Chaotic as it was, excitement ran high and we felt the idea had legs.

Month by month, we built the structure of what we call the Bay Area Leftist Chinese Group (湾区左派中文团体) as a project of Tenant and Neighborhood Councils (TANC), a Bay Area-wide tenant union. Our recurring language socials have been held at art studios, bookstores, the office of the East Bay Democratic Socialists of America (East Bay DSA is a fiscal sponsor of Bay Area Current), and the occasional bar. Initially attendees came from our own social and organizing circles, but more and more people eventually found us through word of mouth or on social media, drawn to our flashy event flyers. At these socials, attendees read from a short Chinese reading on a political subject, leading into an open discussion where they can practice using vocabulary relevant to politics and organizing.

About one-third of active members are native Chinese speakers, attracted to the group’s serious discussions about politics, so while ABCs (American-born Chinese) shore up their language skills and reconnect with a heritage with which they may have a complicated relationship, they learn alongside advanced and native speakers who are also learning about political discourse in China. “Even though I’ve spoken Chinese at home since I was little, I realized that I struggled with basic words outside the household, especially legal or political terminology,” says Eva, who heard about the group after joining the San Francisco chapter of TANC. “Even ‘tenant association’ itself isn’t something I would say day to day with my parents.”

Victor Wang, who is Chinese Australian, agrees. “I didn’t really have a political language in Mandarin. I just didn’t know how to do it. But over the last two years I’ve gotten much better at that.” Victor was one of many from our group who participated in a canvass of San Francisco Chinatown to share information and resources with shop owners and workers to prepare them for potential encounters with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). “We were only able to mobilize because of the group, and because people had participated in practicing the language. The fact that we could go out there and confidently speak to people really dovetails the cultural and political motivations that some of us have.”

Growing turnout soon led us to add a second social each month, so that we now meet once in Oakland and once in San Francisco. Although socials are held primarily in Mandarin, we’re piloting our first Cantonese-only social this February in response to a demand from Cantonese-speaking attendees. To date, over one hundred organizers have trained and honed their Chinese language skills with us, hoping to use them out in the half-million strong Bay Area Chinese community.

Two years later, we were celebrating our second anniversary back at Li Po Cocktail Lounge. In a whirlpool of dancing, loud music, and tacky baijiu cocktails, we read ancient Chinese poems, ate mooncakes and taught each other Chinese drinking games. Two people debated radical interpretations of 20th-century Chinese history. This combination of cultural, political, and educational exchange is characteristic of the language socials.

To become “fried squid” (chǎo yóu yú 炒鱿鱼) means to get fired. “Great Unity” (dà tóng 大同) is a Confucian concept of utopia that has been adopted by the Chinese lesbian community. These are some of the phrases that participants in the socials have learned.

To become “fried squid” (chǎo yóu yú 炒鱿鱼) means to get fired. “Great Unity” (dà tóng 大同) is a Confucian concept of utopia that has been adopted by the Chinese lesbian community. These are some of the phrases that participants in the socials have learned. From the “Lying Flat” manifesto (tǎng píng 躺平), a viral 2021 anti-work blog post, to Luigi Mangione’s manifesto; Chinese literary classics, immigrant poetry, rap lyrics about factory workers, organizing manuals, statements on Palestine — our readings run the gamut of Chinese political and radical literature. Engaging with texts like these serves not only to build the political vocabulary of the socials’ attendees but also attempts to relate our own working-class issues with international cultural perspectives. We are able to move in between serious discussions about the proper translation of political concepts like “autonomous” (as in CHAZ, the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone) or “gentrification,” to learning about stereotypes about Henan Province in China (think China’s Florida Man).

The Bay Area Leftist Chinese Group has since canvassed Oakland Chinatown multiple times as well. One of the biggest surprises of the canvasses was that, when asked, almost all storefronts reported to organizers that no one had come to talk to them about their rights in case of a run-in with ICE — not even groups like the Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce. Chinese business associations have claimed to represent the local Chinese community since the early twentieth century, when being a merchant was an easy way to immigrate to the United States; however, these organizations have often acted as bulwarks for anti-working class politics in the Chinese community. The Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, for example, campaigned against plans to convert the Oakland Courtyard Marriott into a shelter for unhoused people.

Against narratives that Chinese people are forming a new base of conservative politics, Mona W. shared how her Gong Gong (公公, maternal grandfather) showed her that the Chinese community in Oakland is like any other community: curious to engage with any topic that affects their daily lives. “He was elected to be a representative in his building to complain to the landlord when a lot of his neighbors had problems. We would go canvass together and talk to our neighbors about issues with their building. People are very receptive to this kind of thing.”

“Why haven't I been talking to my neighbors more?” asked Mona, rhetorically. “I feel very strongly about this community, I want to give back. I saw this group as a great way to activate organizers in Chinatown who had the language skills to actually talk to our neighbors. The ICE know-your-rights canvass has been a fulfilling way to get people to talk to our elders.”

At our social in November we were joined by a former union organizer from Guangzhou, China. “It was my first time meeting someone who had organized in China before,” said Cathy G., one of the attendees. “It’s been really cool to meet people who are doing Chinese-language organizing, that’s an aspect of organizing that I’ve wanted to learn more about and develop my skills in but just have never found a good space to start practicing.” In an environment where few spaces draw both Asia-born Chinese and overseas-born Chinese, the Bay Area Leftist Chinese Group is a rare meeting point for this politically-minded slice of the community and fellow travelers to engage with working-class Chinese immigrant issues.

The Bay Area Leftist Chinese Group shows it is possible to cohere Chinese diasporic identity not around business interests or shallow cultural markers, but the struggle for dignified life and addressing the material realities through which an ethnic identity is so often experienced.

“I don’t think there are any other groups that are specifically leftist and Chinese. I know a couple graduate students who are Chinese, who are leftists one way or another, but they’re not a group, they’re not trying to organize,” said Bintang, who’s from China and started attending about a year ago. “It’s pretty difficult to find a group of people in the Bay Area who are organized, have a base, and have political takes that I like. This group is a combination of the three.” Victor agrees: “I think if one were to look for a similar space, this is where they would end up.”

If there is anything that the project of the Bay Area Leftist Chinese Group shows, it is the possibility to cohere Chinese diasporic identity not around business interests or shallow cultural markers, but the struggle for dignified life and addressing the material realities through which an ethnic identity is so often experienced.

At a recent social, a first-time attendee remarked: “I’ve heard about these socials, but this is my first time here. I have no idea what is going to happen.” And that’s part of the beauty of the socials — neither do we.