AFTER SCHOOL: Strike is Over — For Now

Teachers will now decide if they'll accept the contract. Learn about the process, and what could come next.

Tenants at 2341 Valley street, a 41-unit building in uptown Oakland, are fighting against squalid conditions, an absent landlord and city bureaucracy. But they’re not giving up.

When BeeBee, a 35-year-old city employee, moved into a new apartment at 2341 Valley Street in 2021, he thought it was strange that his heater wasn’t working in what was advertised as a newly renovated unit.

The apartment is one of 41 units in a run-down building nestled behind the Koreana Plaza Market just off 24th street in uptown Oakland. Real estate developers like to call the area “Koreatown Northgate District,”or “KONO” for short. On the building’s website, the management company BLVD Residential describes the property as having “cutting edge amenities, meticulously-groomed grounds, and a dedicated staff.”

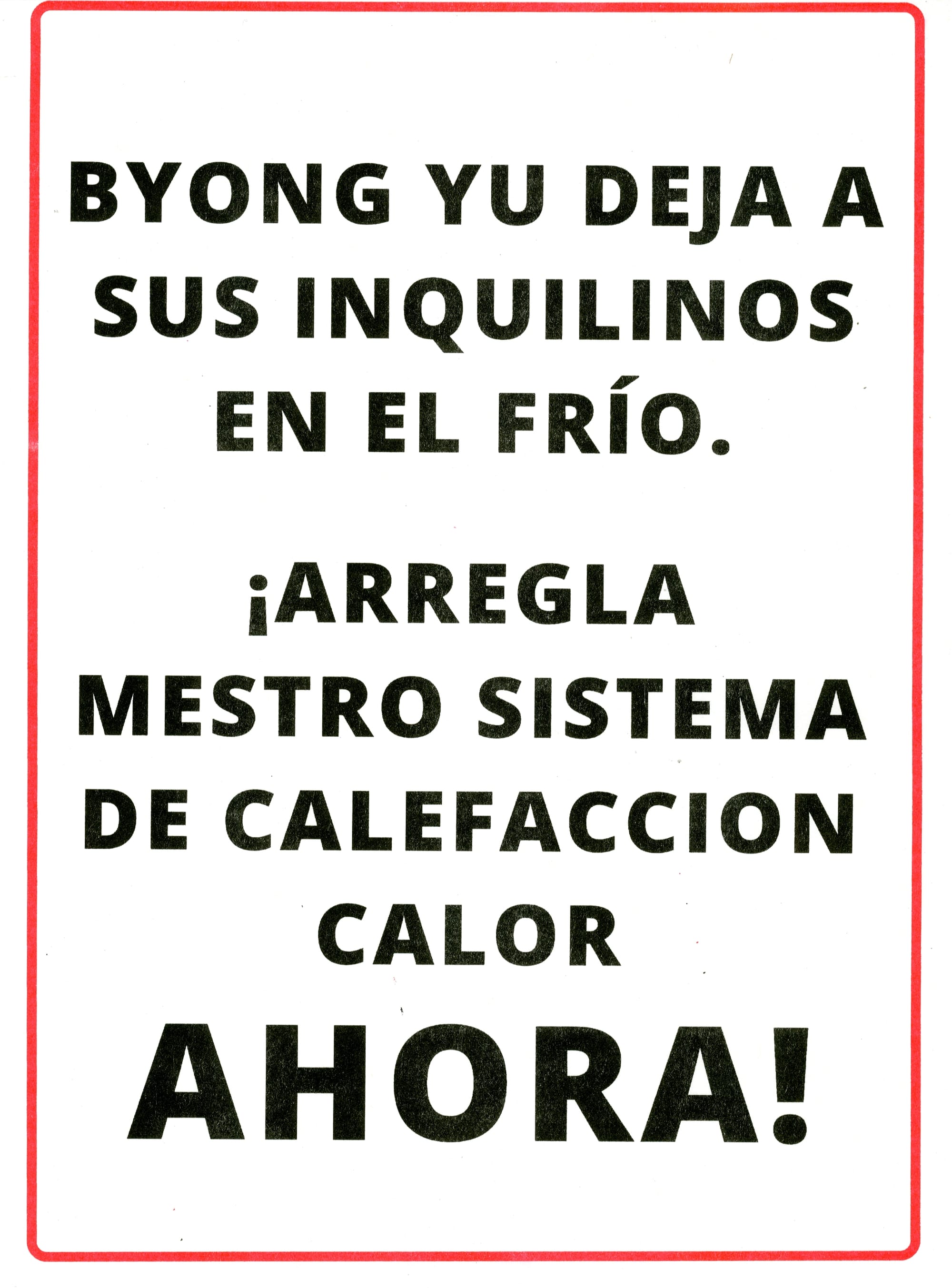

That wasn’t what BeeBee saw there. He had just moved from one apartment building without heat to another — a situation more common for Oakland tenants than one might expect. After talking to his neighbors, he discovered an astonishing fact: some of the residents of Valley Street said that they'd been living without heat for more than a decade.

Little did he know those conversations would escalate into an ongoing building-wide battle for heating and repairs that continues to this day.

BeeBee, who goes by his nickname, immediately notified the landlord about his heat problem and submitted a tenant petition through the Rent Adjustment Program (RAP), requesting a decrease in rent due to a lack of service. RAP is a local government program which mediates disputes between renters and landlords.

That was just the beginning. Soon after, tenants in the building organized and sent a letter to their landlord, Byong Yu, demanding repairs to their units. When the landlord didn’t respond, the tenants collectively submitted RAP petitions to the city. Finally, there was a response. The property manager was required to attend a town hall with residents.

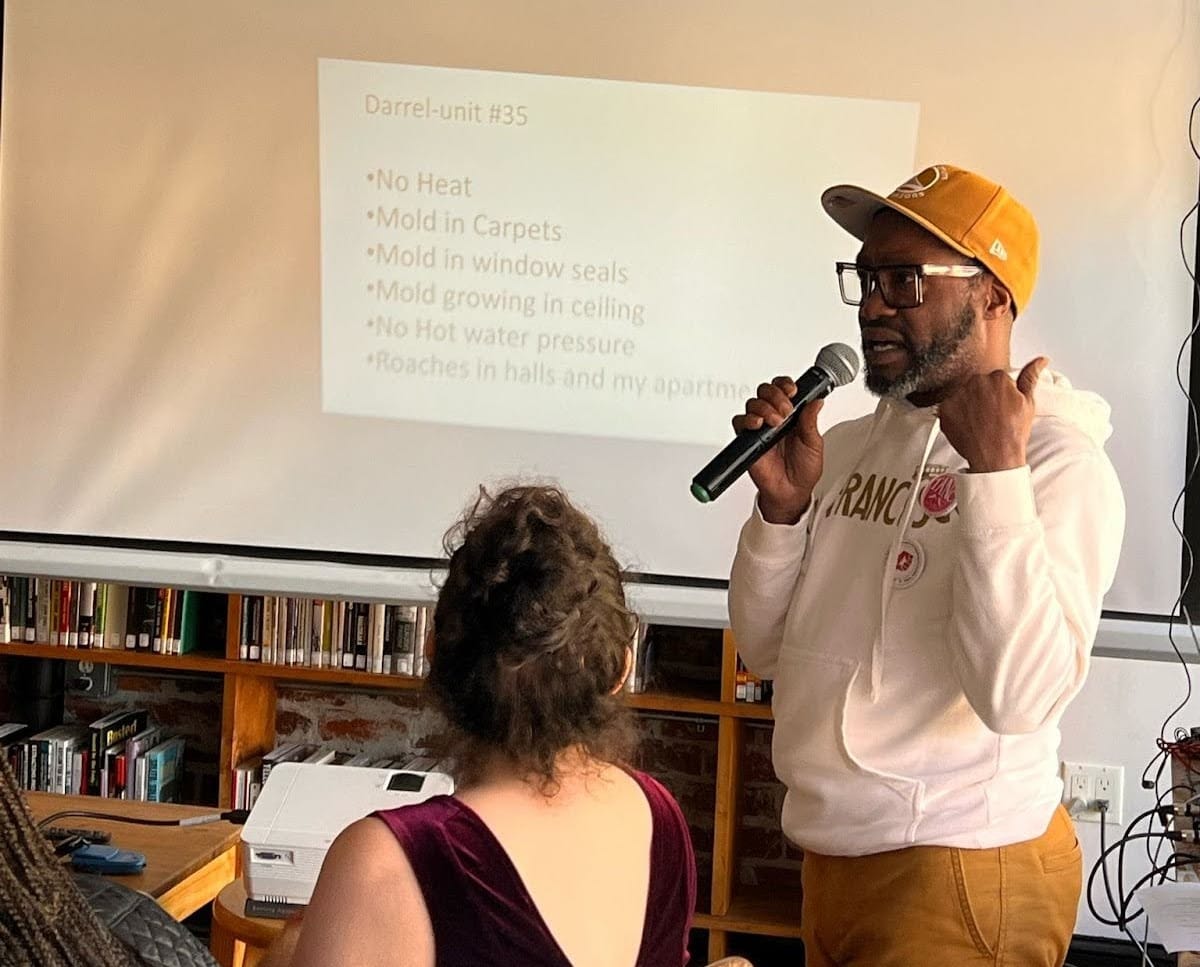

“I never thought myself to be an activist whatsoever,” said long-term tenant Darrel Thigpen. “I was proud of myself. At the town hall I was just going to be the face and the voice for our building and encourage us to speak against [the property manager], which we did.”

Much to the tenants’ dismay, when the long awaited town hall happened, the property manager left the meeting after only five minutes.

I met BeeBee, and other residents of Valley Street, through my work with Tenant and Neighborhood Councils (TANC), which eventually supported the tenants organizing at the building. Their experience makes me wonder how many landlords, property managers, and city petitions one needs to go through for basic repairs in Oakland. The residents of Valley Street are still waiting for an answer. As of September 2025, none of the occupied units have working heating systems, and at least one has had the heater removed entirely.

Despite living more than a decade without heat, Valley Street tenants say things became truly unbearable after BLVD Residential took over property management in late 2021. Specifically, after the old residential manager left her position and wasn’t replaced.

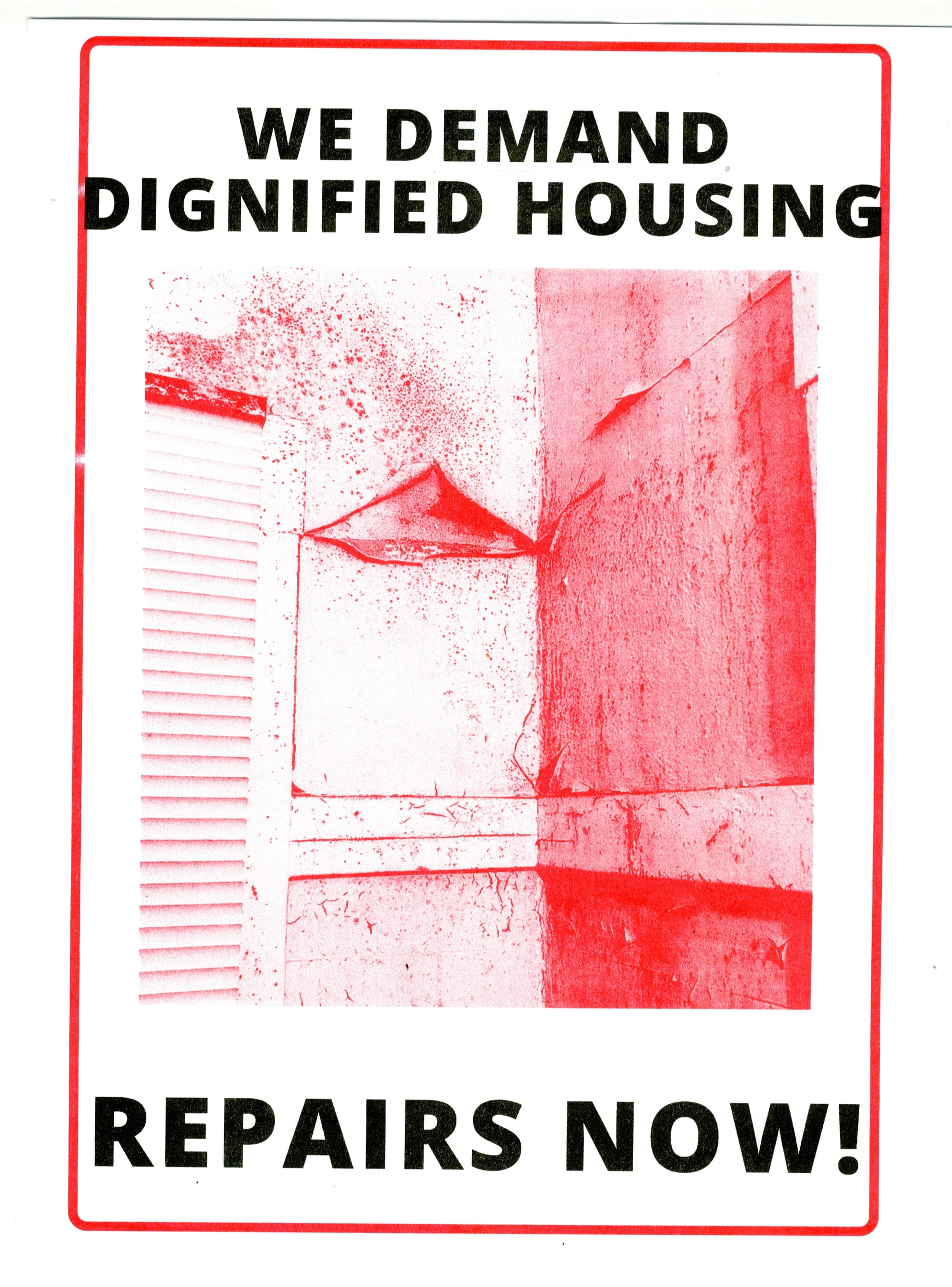

Soon after, trash built up around the complex, and pests became a recurrent issue. Apartment buildings with over 16 units legally require a residential manager to care for the property, according to California Civil Code (Title 25, Section 42). Tenants have since reported additional problems, like mold and recurring leaks.

Current reached out to BLVD for comment on these issues. BLVD provided no comment, though they noted that the regional manager who attended the RAP hearings and town hall no longer works for them.

Darrel said that a lack of heat since about 2012 wasn’t what broke him — it was a roach infestation that did it.

“When I came from the Midwest I just assumed it was normal to not have heat. So for me, it was the insects and rodents I was always bothered by, and my electric bill,” Darrel said. “Because on those cold days we would blow those electric heaters up.”

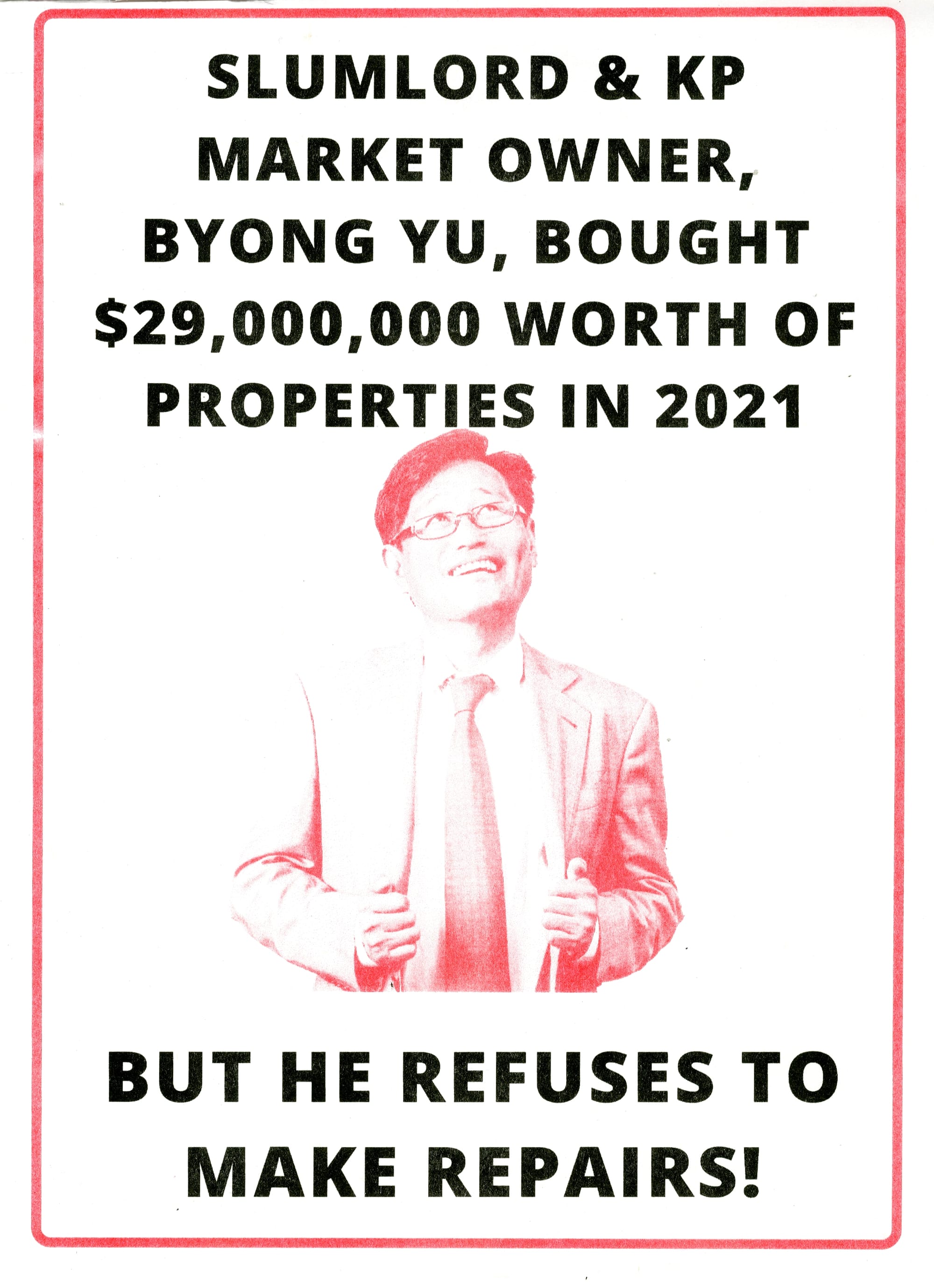

Both the building and the Koreana Plaza Market behind it are owned by landlord Byong Yu, who owns a substantial property portfolio of residential and commercial properties across the East Bay and near Sacramento.

Yu, a self-described businessman who claims he pulled himself up by his bootstraps, through trial and tribulation, bought KP Market from his sister in 1989. In 2021, he purchased over $29 million dollars worth of additional residential properties. In 2024, Yu gave a $10,000 donation to the campaign to recall Pamela Price, according to KQED. All the while, his Valley street property sat in disrepair.

In a 2018 interview with Comstock’s Magazine, he said that when starting a new business, “[I have] to be willing to sacrifice anything to make it happen. That’s the really hard part.” In the eyes of his tenants, Yu is nothing more than an elusive property speculator. It seems others can do the sacrificing.

Current also reached out to Yu for comment, but received no response.

When Darrel saw renovations happening at Yu’s grocery store — like the installation of a fence around the parking lot — while severe maintenance issues persisted at Valley Street, he realized the situation wasn’t right. But for Darrel, the low rent offered him an opportunity he couldn’t give up.

“It allowed me to stay in Oakland and experiment with my career, life goals, and everything,” he said.

Skyrocketing rent profiteering across the Bay Area over the last decade has meant that many within the building — and across the whole Bay — have chosen to stay put despite the persistent maintenance problems from landlords who cut costs and treat their properties as speculative assets instead of homes.

Seeking support to deal with absent management, Darrel and his neighbor Irena M. (who preferred not to share her full name) joined local tenant union, TANC. TANC focuses on helping tenants organize around habitability issues and form building-wide tenant associations that can connect across the Bay Area.

With TANC’s help, Darrel and Irena began organizing their building by holding regular meetings to discuss pressuring the landlord to make repairs. By gathering and listening to their neighbors' grievances they were able to compile demands to write a letter to send to Yu and BLVD. After they mailed out their collective demands, a few tenants even stopped paying rent and eventually the majority of residents submitted a collective petition to RAP.

But gaining enough confidence to take on their landlord didn’t happen overnight.

“What TANC did for us was lift us up as leaders within our building,” Darrel said. “It took so long for us because we thought we were alone, and even like going to the TANC meetings, hearing other buildings' problems and stories…”

“That was exciting,” Irena chimed in.

“It set fire here,” Darrel pointed to his heart. “We’re not the only building that [landlords] mistreat — and that’s not okay. I didn’t know it was this common.”

Receiving encouragement and sharing advice with other organizing tenants was key to building up their confidence.

Melvis, 58, another tenant in the building who preferred to go by his nickname, said the experience from the union helped the tenants stay focused and directed. When the building began holding regular meetings, they decided on the name Valley Street Tenant Council.

“TANC showed up at the right time, at the right moment,” Melvis said. “We didn’t know what to do. Otherwise we might not be here right now. We might be out already.”

In November 2022, the Valley Street Tenant Council sent six demand letters asking for basic repairs between Yu and BLVD: they received no response. Deciding to step up the pressure with the support and resources from TANC, the tenants held two pickets at his grocery store and then collectively filed petitions with Oakland’s RAP board in 2023. Throughout this struggle, some tenants even decided to stop paying rent to build up pressure against Yu. With 16 petitions now filed, and consolidated by the city into one case, they hoped something would change.

The RAP Board serves both landlords and tenants who can file petitions resulting in counseling or mediation by a hearing officer. Tenants can petition for a rent reduction based on loss of services, code violations, or incorrectly filed rent increases. Similarly, landlords can use the program to petition for rent increases outside of the allowable increase amount.

BeeBee, back in 2021, had already successfully filed an individual petition receiving an indefinite rent reduction that continues to this day.

The rent reductions won through a RAP petition process theoretically provide an incentive for landlords to make repairs. But there is no guarantee any repairs are actually made. And when it comes to basic repairs, a small reduction in rent hardly feels like a win.

During the RAP process, tension heightened when the property manager claimed tenants would have to leave the building so that the company could complete extensive repairs. With a record of absent communication and neglect from BLVD, tenants were left wondering what would happen to them if they moved out. Would they be able to return? Would the city be able to secure and enforce their right to move back into their homes?

There were two RAP hearings held with the Valley tenants; the first on December 4th, 2023, and the second on February 26th, 2024. No landlord representatives showed up to the first hearing. Without their presence, the hearing would have sided in the tenants’ favor. But to the tenants’ surprise, a regional manager from BLVD Residential appeared at the second hearing.

During this hearing, the BLVD representative told RAP hearing officer Linda Moroz that they had posted 33 move-out negotiation agreements on tenants’ doors in May 2023 and insisted the tenants needed to move out in order to make major repairs. According to the RAP hearing “Order and Case” document shared with the Current, this was the first time tenants had heard anything about moving out for repairs. Throughout the hearing, BLVD never specified what the repairs were or when they would likely be completed, nor did they provide any permits or other evidence of repairs.

The tenants interpreted things a little differently. They understood the move-out notices as an informal eviction threat. With no further communication regarding repairs, permitting, or buy-outs following the notices, the tenants’ believed that management was using the illusion of improvements as a tool to push them out for good.

In the face of these differing interpretations, the RAP hearing officer decided to give talking a chance: Moroz mandated a town hall meeting, to be held within the next 30 days, to clearly communicate the purpose behind these 33 move-out notices and the move-out negotiation process.

“BLVD was supposed to arrange it, but we knew right off the bat, we knew immediately let’s just coordinate this,” Irena said, speaking to management's reluctance to act.

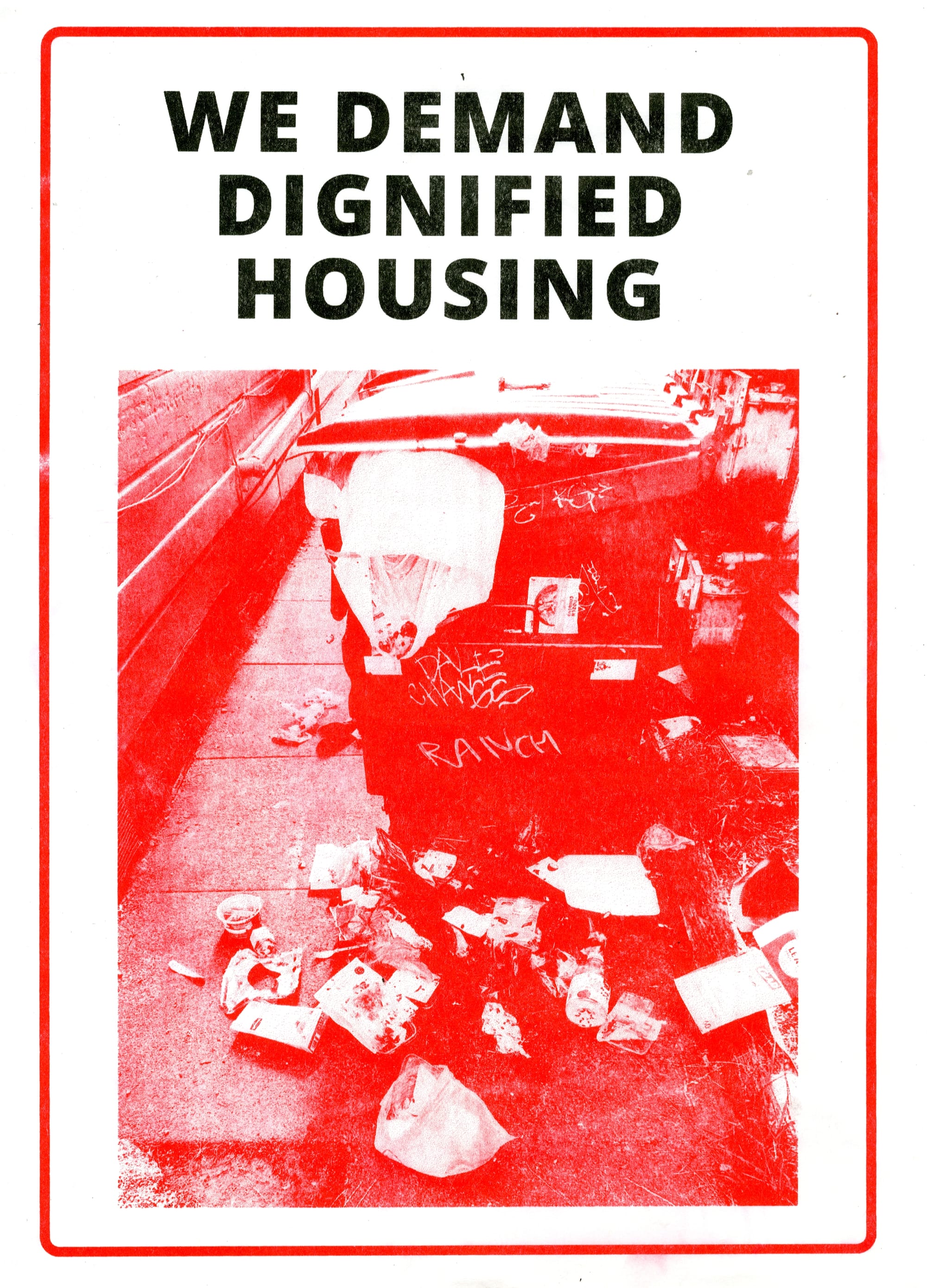

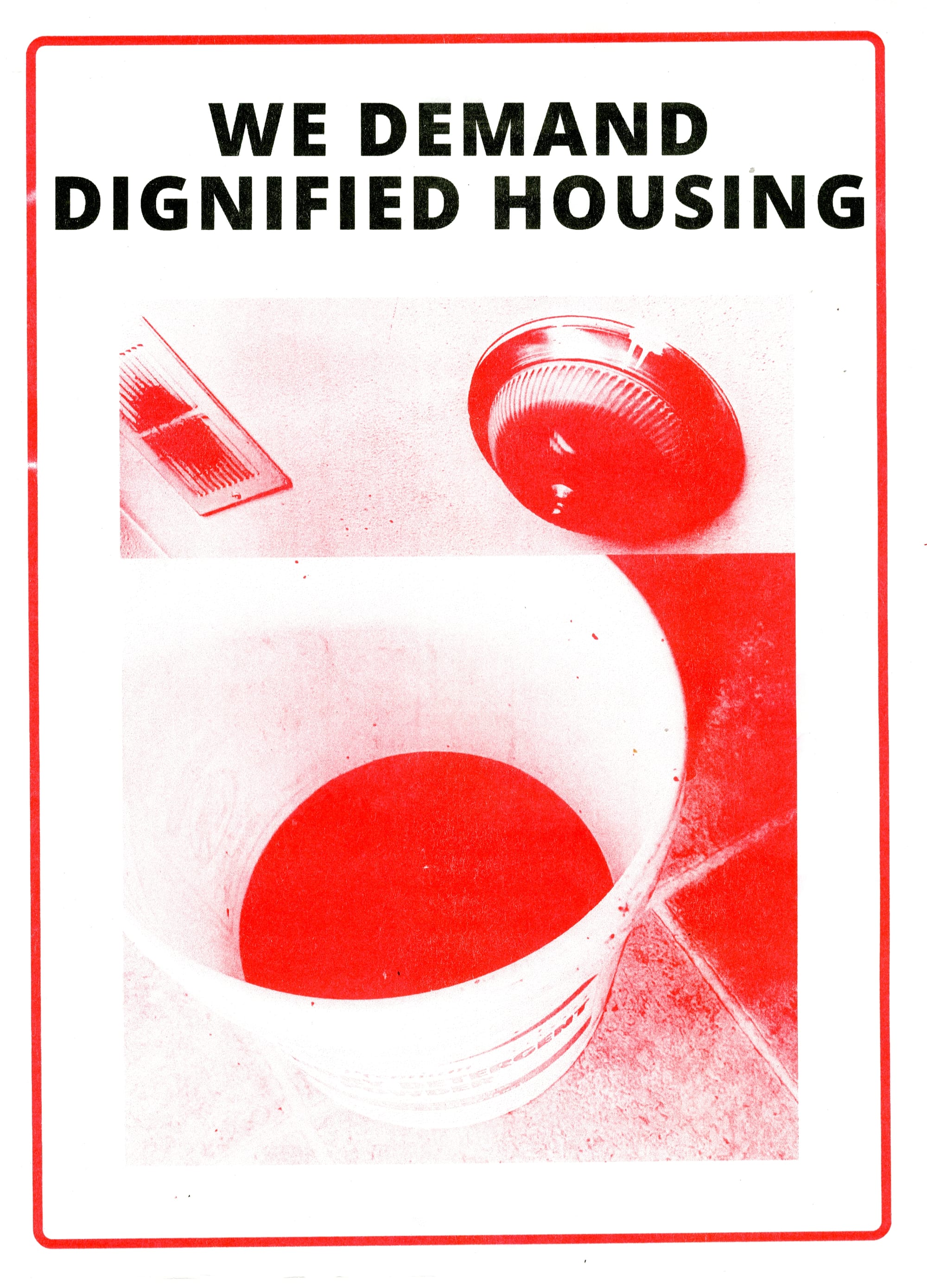

With the help of their TANC chapter, the tenants set up the meeting at a community space. As the building is majority Spanish language speakers, they hired Spanish language interpreters and brought dinner to share using union funds. They prepared an agenda to discuss managerial changes and expectations beyond move-out negotiation logistics, and hung posters with pictures of their current living conditions on the walls.

Posters prepared by Valley Street tenants and TANC organizers for the town hall meeting between tenants and property management, mandated through the RAP process. (Cecelia Shaw)

The BLVD property manager, who no longer works for the company, was surprised to see a room full of tenants and TANC organizers along with the two representatives from the City Housing & Development Department. She didn't want to listen to the tenants grievances or make negotiations — she was there to discuss the move-out process.

Within five minutes of the meeting, the property manager left the room. She claimed she was going to call the “real” property manager, but left without another word in the middle of tenant testimonials and didn’t show up again. No other alleged property manager has since emerged.

“Her leaving proved our point to those people from the city,” Darrel said of their unwillingness to communicate with tenants.

Even without the property manager, the tenants gave their testimony. The feeling in the room was uneasy as they were left wondering what to do in BLVD’s absence. With only the city representatives, Kelly Hoffman and Corean Todd, present, everyone discussed move-out negotiations.

The tenants asked hard questions and the city gave difficult answers. If the tenants agreed to move out, it would be nearly impossible to ensure they could return at the same rents within a reasonable amount of time, let alone move back in at all. Any number of setbacks with contractors could delay repairs and prevent the owner from letting tenants back in.

Temporary relocation services through the city of Oakland could only guarantee $7,000 for one-bedroom apartments (plus $2,500 for children, people with disabilities, or seniors) — no more than a deposit and two month's rent of market value rent. Payments above that number would require negotiations with the absentee owner. Looking for a temporary place to stay would fall on the tenants. After the repairs are made, it’s the landlord’s responsibility to communicate with the displaced tenant their option to move back in. No one liked hearing that.

“There's a good faith belief that we will have consistent, clear communication. Historically, we have not had that whatsoever,” Irena said during the townhall. She wanted to know who in the city could enforce communication — or action — from the landlord.

To the tenants, moving back into their rent-controlled units after extensive repairs and investment on a decrepit building seemed like a long shot. It just wasn’t imaginable for all the factors to align in their favor. The process relies on good faith actors (in particular property management and landlords) and isn’t easily enforced by the city.

Today, Oakland public records indicate the Valley Street RAP cases are closed and no building permits have been filed on the part of BLVD. The tenants still haven’t seen much movement from management, but they say they themselves have acted with dignity.

“I feel like I stood up for something, and I fought for it. And the city was there, the property manager was there. So for me, just accomplished as an activist,” Darrel said about the town hall.

BeeBee also thought the tenants' organizing had left an impact.

“It affected the tenants, workers, and the community. I run into people who still don't shop at KP because of what they read in the Oaklandside or [the pickets they] saw at KP,” he said.

Although BLVD Residential provided no further comment on this story, they did inform Current that the regional manager who attended the town hall no longer works for them.

As for a new manager, BeeBee said, “I’ll believe he exists when I see him.”

Activity among tenants has slowed down, but several mentioned they would like to start meeting again. Some suggested a pancake breakfast, some just wanted to meet up, and a few would even like to picket Yu’s store again. As they navigate the contradictions of the speculative nature of the place they call home, there’s still a clear consensus amongst them — that the fight for dignified housing isn’t over yet.